Category: Notes

Pehle toh kabhi kabhi gham tha… And then came Altaf Raja

These are bad times.

Trump is creating havoc across the world. Our vishwaguru affiliations are taking a beating. Bangladesh doesn’t want to play in India. Neha Kakkar is still singing.

These are really bad times.

Now, I know there is this terrible terrible urge to hang our heads in despair and feel hopelessly bad about our existences. It does come naturally to most of us, especially after seeing Veer Pahariya as an actor. But you know what, life is not that black, despite how bleak things appear. One can either feel utterly depressed. Or, one can invoke the name of Altaf Raja to make it all disappear. Seriously.

Altaf Raja who, do I hear? For those not in the know, Altaf Raja was the singular reason why the cassette players of the 1990s were mobbed, mauled and molested, day in and day out. Altaf Raja was the demi-god of the autodrivers, their secret man-crush, their muse. Altaf Raja was the snazzy sultan, the ritzy rajah that the entire B-grade population of India wanted to be. But to top it all, Altaf Raja was what kept the people across the country going, giving them hope and optimism, as they sung his songs in the trains, collecting monies for charity, in most cases their own charity.

The first half of the 90s was an exciting period in the life of India. The skies were opening up. The reforms were taking off. We were a bemused and overwhelmed nation, getting exposed to an MTV which played music and a Manmohan Singh who had a voice, amongst other things. The divide between the rich and the poor was beginning to get drastically wider. Rishi Kapoor was still wearing Woolmark-approved pure wool turtlenecks, dancing around trees, and Mithun Chakraborty was singing Gutar Gutar in Dalaal. Not that the last two statements had anything to do with each other.

It was during these times that Altaf Raja made an appearance in the Indian stratosphere. Tum toh thehre pardesi, saath kya nibhaoge, he said it on behalf of the country in his first album in 1996, mouthing the concern that the economic reforms were not to stay forever. Subah pehli gaadi se ghar ko laut jaaoge, that is.

But then again, lest you misunderstand him, it was just a healthy expression of anxiety, and not pessimism. Considering in that very album, Altaf presented the enthusiasm and exuberance of the nation, willing to take on the world: Woh bhi anjaan thi, main bhi anjaan tha. Uss se vaada na tha, kuch iraada na tha. Bas yun hi darr-ling keh diya. Yaaron maine panga le liya. Panga Le Liya summed it up brilliantly. Pokharan-II, the Indian nuclear tests happened soon thereafter.

And THIS – the eternal understanding of his environment and its impact – is what makes Altaf Raja relevant all over again in our lives. Yes, the times are tough. From pathetic rapes to pitiable rappers, from a silent PM to an over-zealous wannabe, from Kalmadi’s fistulas to Kejriwal’s frictions, we have issues and diversions. But we need to embrace our surroundings. And wait. Patiently. Because that is the right thing to do. Thoda intezaar ka mazaa leejiye, sang our man in Shapath. That’s the mantra to live by. Wait and watch, and enjoy the downtime. All material conditions, positive or negative, are temporary. This, too, shall pass. Btw, for the fans of geriatric gyrations, the song has Jackie Shroff and Mithun Chakraborty shaking it with the ladies at the bar. That, too, did pass.

His teachings, though, are not restricted to just helping people cope with the larger issues. Altaf Raja has created many a sparkling gem that are relevant to us in our everyday lives across audiences. Even more so in this day and age, when everything around us is getting redefined and restructured. Refer to the lucidity with which he discusses the complexities of the gender roles and the set of social and behavioral norms that are considered appropriate in the context of the modern times. Biwi hai cheez sajawat ki. Biwi se ghar ko sajaate hain. Sautan ka shauq purana hai. Sautan ko sar pe bithate hain. Bharti nahin niyat sautan se. Sautan ki sautan late hain. Balle balle, oh yaara balle balle. Wow Yeah. Wow Yeah. Brilliantly put. Sajawat. Aesthetics. This is why the purists love him.

The most pertinent message of Altaf Raja for his audiences, however, is in this timeless creation called Kar Lo Pyaar. There are discords and disputes all over. Conflicts have divided the globe. The world is fighting a furious war with itself. And I just used three sentences with exactly the same meaning. Precisely the reason why the world needs to hear these immortal lines in his mellifluous voice. Kar lo pyaar, kar lo pyaar, kar lo pyaar, kar lo pyaar. Pyaar gazab ki cheez hai padh lo aaj subah ka parcha. Pyaar karoge muft mein ho jaayega yaaron charcha. This is poetry at exceptionally sublime levels. No other song in the world has EVER tried rhyming charcha with parcha.

Wikipedia says Altaf Raja has had a mix of twenty-three film and non-film albums so far. But none of this matters eventually. Because it is not about his songs or the albums. It is about the man. Who goes far beyond the songs or the albums or the hits or the platinum discs. Altaf Raja is a concept. He is the victory of the mundane over the elite, of penury over pomp, of the coarse over cultivated, and of hopes over realities.

Thank you for taking the panga, sir!

(Originally published on firstpost.com)

A Chhath Homecoming at Chowpatty

I have never been shy of my Bihari identity or affiliations, but I have not really been too pronounced about following the festivals and rituals of the land. And the detachment, I must confess, has been cultivated.

Blame it on the 90s.

While I’m no socio-political-cultural commentator, I would want to believe we were the last of the generation following the Nehruvian socialism and secularism, and accepting/ embracing our own traditions kind of made us feel a bit guilty about partnering with the right-wing activism that was beginning to take off in this period. Also, with Liberalisation and Globalisation becoming the new buzz words, people like me who became an integral part of the media landscape of the country found ourselves busy shaking and shaping perceptions, and perhaps had no time for what we perceived as reminiscent of the old world order, the non-modern, fuddy-duddy small town universe, that we had consciously left to become mini-metropolises unto ourselves.

Lost between our identities of the past and the future, we became a watered-down version of ourselves. Urbane, articulate, but oddly rootless, letting the noise of the new drown out the voice of the old. In my defence, our wokeism, for want of a better word, was guided by pure idealism, but in the process, we were ready to let go of what was us, what defined the core of us. We did not want to take note of what the “new and improved” label on us was actually stuck to!

We were idiots.

No surprises, therefore, that the last time I attended a Chhath Puja was a couple of decades back! Of course, I’ve always been a loud votary of the puja, how Chhath is perhaps the only Hindu festival which is caste and gender agnostic, how there are no rituals, no scriptures involved, how the devotees worship both the setting and the rising sun, how it represents a bulk of India at its agrarian best, but I kept myself away from the actual festival.

Till this year, that is.

I got an invite to attend the Chhath Puja in Mumbai. I wasn’t too sure initially, worried that my presence would feel performative, unsure if I would be observing or actually belonging. And then, almost without warning, an epiphany hit me hard. The so-called old world order that I came from was as much me as the newness I wanted it to adopt. From running at the slushy shores of the Ganges at Patna’s Pahalwan Ghat to now partaking in the celebrations at Mumbai’s iconic Chowpatty, it wasn’t just distant geographies connecting, but my thoughts and identities perhaps finding common ground.

I was ready to get my feet wet again.

The atmosphere at Chowpatty was electric, the devotion real. Chhath has a way of turning every shore into a sacred space. Despite an errant wave or two playing hopscotch, and the sea of people around, there was something deeply calming about it all. The sincerity and the faith, the smell of the wet sand, the sight of the thekuas, the vratins having private conversations with the sun god, the flicker of the diyas… In no time, I had gone back to where I belonged.

In no time, I could see where I still do belong!

My father, those could-have-been-hugs, and Chitragupt

When I was growing up in Patna as a part of a large middle-class family, with a whole load of uncles and aunts, beautiful people, them all, staying under the same roof along with this set of four siblings that we were (Mummy created lots of babies while managing a household and playing a professor, but that’s for another post!), I don’t think there was any scope, or space, for some sort of a personal bonding with my father. And I don’t say this as a complaint. This is how things were. It was a large family. He was rigidly righteous and decisively democratic about sharing his affection with everybody, and definitely not concentrating only on his children. We were happy with what we got, and we got a lot. Even if he never verbalised it, even if he wasn’t loud about his feelings, even if he played the stricter parent, we knew.

The uncles and aunts got married. We got busy with our dreams and aspirations, eventually leaving home for colleges in cities far away. It was a pain departing every single time I went back to the University. Mummy would hide a tear, or two. I would act all grown up and macho. Papa would remain stoic. I suspect we even attempted a couple of awkward could-have-been-hugs in this phase of our lives.

The parents continued to teach at the Patna University till they both retired. The kids continued with their journeys. Considering the world would have stopped revolving if I were to take leave from my job at MTV, I didn’t really go home as often as I would have wanted to after I started working. Every time that I did, I would notice a fresh wrinkle, a new strand of grey, and a very charming couple growing old together, with the kind of love that is tough to acquire or achieve. There was one noticeable change in Papa, though. He had kind of started mellowing both as a person and a parent. But the expression of endearment still appeared the same. As muted. As sweet. He would now shake hands while seeing me off, his hand staying on mine for a couple of extra seconds. Or them last moment jaldi-jaao-flight-nikal-jaayegi hugs with quick, warm pats on the back.

I got them to Mumbai. The arrangement was that they would live independently, how they liked it, two buildings away from mine.

Mummy decided to embrace the retirement the way she wanted it, doing nothing (though I suspect she wouldn’t have said no to making a few more babies, her most favourite thing in the world). Papa decided to do everything that he wanted to. From playing Manoj Tiwary’s father in Bhojpuri films (Rinkiya ke Papa’s Papa is my Papa, thank you) to selling Chyawanprash with Alok Nath on teleshopping networks, and succeeding to embarrass me in the middle of the night every single night for months on national TV, to creating radio plays to writing books! At 70-something, he was glued to the computer, not to play Solitaire, but to research and write, and write and research.

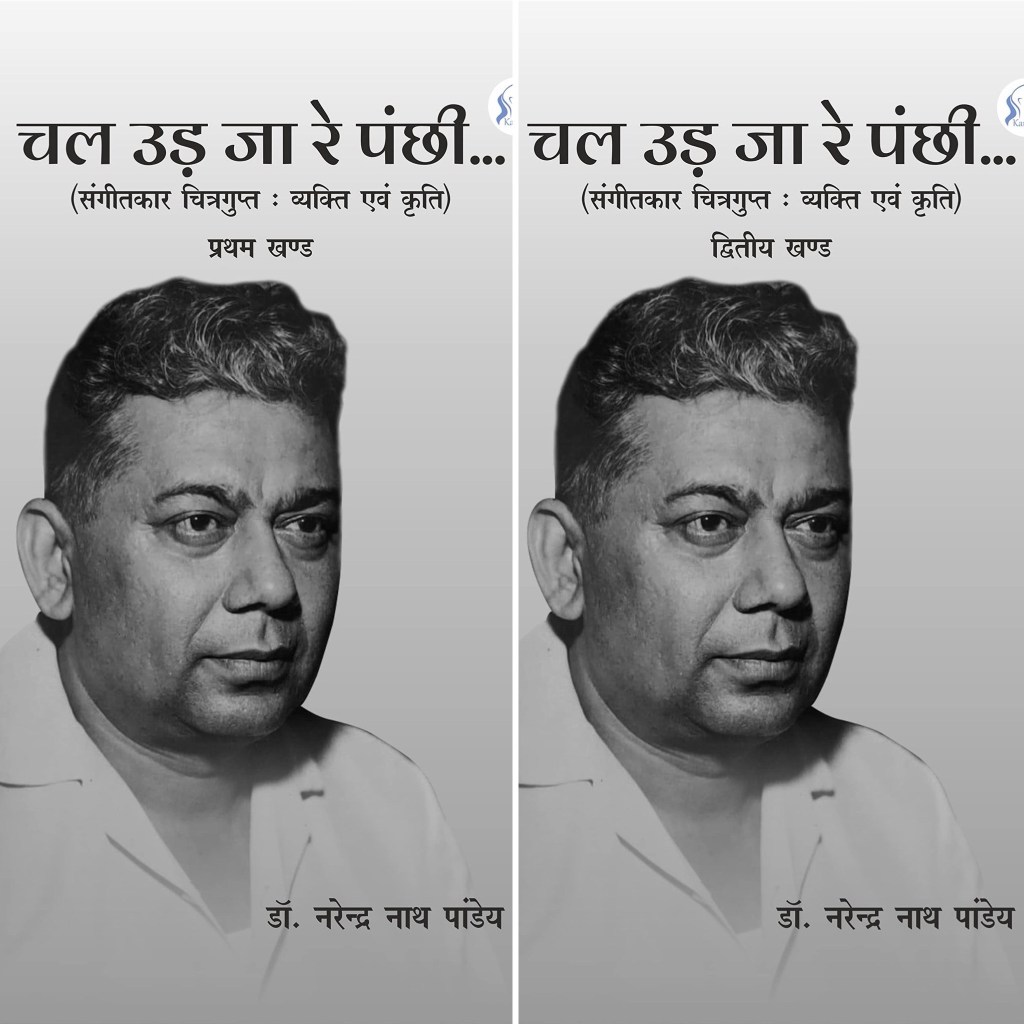

Chal Ud Ja Re Panchhi, Dr. Narendra Nath Pandey’s third book, out now on Amazon, is a voluminous 2-part biography of yesteryear’s music director Chitragupt, of Teri Duniya Se Door Chale Ho Ke Majboor and Daga Daga Vai Vai Vai fame. Backed by more than three years of intense research, blessed by Lata Mangeshkar, with a foreword by Vishal Bhardwaj, and interviews with prominent music personalities, the book would be particularly useful to the aficionados and students of old Hindi film music, researchers and musicologists. Here’s the link for those who are interested: https://www.amazon.in/dp/939088568X?ref=myi_title_dp

I kind of helped with the soft launch of the book at LitChowk in Indore a few months back. It was surreal sharing stage with Papa, referring to him as Dr. Pandey, with Mummy in the audience. This was the first time that his beautiful labour of love was being presented to the world. Dressed in black, matching the fresh coat of black in his hair, my dapper dad talked effortlessly and earnestly about his favourite music director’s journey, complete with facts, anecdotes and explanations, and a lot of wonderful music. The audience lapped it up.

When we went backstage after the talk, I extended my hand for a handshake, congratulating him for a job well done. He looked at me, and all my readings of all his expressions all my life failed me at that one moment. Papa pulled me towards him, and gave me the tightest, warmest hug that could be.

It was my turn to not being able to verbalise what I felt. Also, I had to rush to the water cooler. There was something in my eyes.

Revisiting JJWS – the OG Archies

1992 saw the release of Meera Ka Mohan, headlined by Avinash Wadhawan, featuring the chart-busting disco-devotional O Krishna You Are The Greatest Musician of the World. Keeping the cine-goers glued to the theatres also was Kumar Sanu crooning In The Morning By The Sea for Ronit Roy and friends in Jaan Tere Naam. The year witnessed SRK doing one of his earliest roles as a hero in Hema Malini’s directorial debut Dil Aashna Hai. Then there was Amrish Puri singing Shom Shom Shamo Sha while playing a trumpet, sitar and drums in Anil Sharma’s Tehelka. Govinda and David Dhawan found each other with Shola aur Shabnam, and Madhuri Dixit discovered her breasts with Dhak Dhak Karne Laga in Beta. For people with more discerning taste, Meenakshi Sheshadri referred to Chiranjeevi as Tota Mere Tota in Aaj Ka Gundaraj, Rahul Roy became a tiger in Junoon and Salman Khan wore a golden colored wig to pirouette with his inner Thor in Suryavanshi. Obviously, some of us had fun growing up.

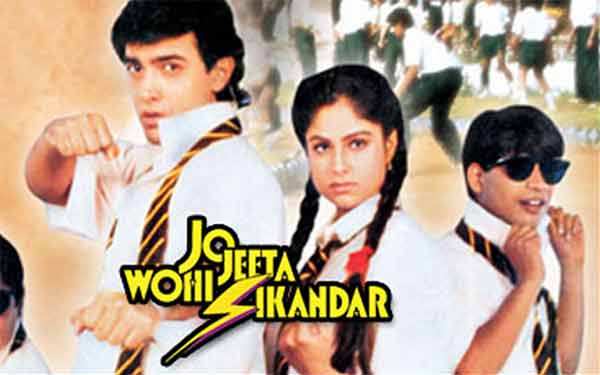

1992 was also the year of Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar.

The brilliant Mansoor Khan’s second cinematic outing offered a straightforward story. Sanju is a happy-go-lucky boy, smoking cigarettes and bunking classes, leading a carefree life with his carefree friends in Dehradun. His father Ramlal is the sports teacher at the lowest-on-the-rung Model School. There is a clear class divide between the hill town’s elite schools and their local counterparts – nowhere more apparent than the bicycle race on which the movie hinges. When Ratan, Sanju’s elder brother, has a near-fatal accident while preparing for the inter-college race, it becomes Sanju’s responsibility to take over and compete against Shekhar Malhotra, the flashy champion from the flashy Rajput College. Sanju feels the combined agony of his father and brother, turns around, prepares for the race, wins it, and in the process, discovers himself. Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar. End of story.

But despite this very basic storyline, Jo Jeeta… is perhaps the only movie from 1992 to have survived the test of time 30 years since its release. If you happen to watch anything made that year, you will be taken to a world that is distant, jagged, and often embarrassing. The stencilled heroes waltz between the plastic and the profane, flaunting a rather coarse machismo challenging Mr Richter. The heroines wear conical bras, their Saroj-Khan-nominated cleavages heaving extra hard to seduce them heartless heroes and their ripped muscles. The villains are odd, outlandish, and over-the-top, and perhaps the most entertaining architectural remains of the era gone by. The films speak a language that is totally different from anything around or about us at present.

NOT Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar.

Tag it with the “Smoking is Injurious to Health” warning, cut Deepak Tijori’s hair short, ignore some of the fashion faux pas that are the vestiges of the horrible ’80s, and hell, it will pass off as the real deal even now! It remains as fresh and relevant today as it was then. The simple story, the key messaging and its aftereffects, the lovely everyday characters, the bonding and affiliations, the victories and defeats, the joys and sorrows, the aspirations and ambitions… all of it is universal and identifiable. Now, and perhaps even 30 years from today!

In the multi-layered backdrop of teenage yearnings, of silent, unrequited and failed romances, of the angst stemming from class divides between the haves and have-nots, Khan recreates the world of The Archies in an Indian avatar, sans any artificial pompoms and cheerleaders. Just a dash of Farah Khan and Jatin-Lalit freshness, the velvety voice of Udit Narayan, the vulnerability and innocence of Ayesha Jhulka, Aditya Lakhia and Deven Bhojani, and, of course, the charm of Aamir Khan as Sanju.

Sanju is vain, selfish, and twisted. He exploits Anjali, his best friend, because he knows she is secretly in love with him. He takes Maqsood and Ghanshu, his close confidantes and partners in crime, for granted while playing their ring leader. He consciously cons Devika – the shimmering, sizzling Pooja Bedi – into believing he is the son of the multi-millionaire Thapar. He actually instigates a fight at his father’s cafe and gets it totalled. Sanju is everything a hero should not be.

But there is something about Sanju that only heroes can be. He is a non-conformist. The defiant cry of Jo Sab Karte Hain Yaaron, Woh Kyon Hum Tum Karein is inspiring if you don’t subscribe to the thought, and comforting if you do. Your heart beats for Sanju because there is a little bit of him in all of us. Or there is a little bit of Sanju that all of us want to be. Precisely why you feel sorry for him when he gets exposed in front of Devika. Or when Thapar yells at him in the presence of all of his guests. Or when Ramlal throws him out of the house.

Ramlal is a strict father. He is also guilty of playing favourites. Which explains Sanju’s continued insubordination and insolence. The father is the system, the man. Sanju is the rebel, while Ratan follows the norm. To such an extent that when Sanju leads the pack in the Sheher Ki Pariyon Ke song, the elder brother voluntarily plays the second fiddle. The love between the siblings is not cardboard, melodramatic, or overtly emotional. And yet, when Ratan is admitted to the hospital, Rooth Ke Humse Kabhi tugs at your heartstrings and tears the ventricles out.

The rich-poor divide and the continuous hostility toward the poor – the pajama chhap – is a recurring theme in the film. Khan chooses a rather interesting cinematic device to reveal Sanju’s poverty to Devika. A dance sequence featuring a Chaplinesque Sanju, complete with tattered clothes. But you see the light at the end of the tunnel when you hear the Model School team mouthing the lines, Yeh Maana Abhi Hain Khaali Haath, Na Honge Sada Yahi Din Raat, Kabhi Toh Banegi Apni Baat, Arre Yaaron, Mere Pyaaron. It is almost poetic, Devika’s changing expressions as Sanju lives up his penury!

Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar appeared at a time when the reforms that would result in opening up our economy had just been initiated. We were still reeling from the garishness of the ’80s, but the theme of class inequality that populated the films of the ’70s still endured. Jo Jeeta… was perhaps the first film that brought home class inequality the way many of us actually experienced it. Not the way Amitabh Bachchan did, raging against the machine and the system. You weren’t fighting for scraps on the streets or refusing to pick coins off the road, but you did feel a twinge of jealousy when you saw someone in a nice car you couldn’t own.

For an entire generation of cine-goers figuring themselves in the 1990s, Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar was, therefore, not just a film. It inspired us to stay happy, take risks, not follow the norm, know and appreciate the value of success, and, well, work towards it. Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar was, in many ways, a lesson in life. And one realises this even more so now, looking back.

POST SCRIPT: 1992 was also the year a numerically sound Ajay Devgan checked on the audiences’ Jigar, Sunil Shetty made his debut in Balwan, Akshay Kumar started playing the Khiladi, and Sanjay Dutt figured the joys of romancing the wet sari in Yalgaar. We were one lucky lot, clearly! :)

The importance of being Bappi Lahiri

While Bappi Lahiri would continue to be celebrated for his very strong imprint on the musical legacy of India, his larger contribution in the social space remains as melodic and charming, if not more, with its own pronounced rhythm and bass. Because despite seemingly being a 1970s and 1980s music icon, Bappi Da inadvertently became the new India story for the generation that came into its own in the 1990s.

With the advent of Liberalisation and Globalisation, the changes that us 90s kids were witnessing were sudden and far too many, and my generation was scrambling for home grown icons that we could take pride in, and call our own. Somebody associated with beats of disco that were moving towards obsolescence already, some very brazen ctrl-c-ctrl-v accusations, and a pronounced regional accent in the Queen’s language perhaps was not what the doctor would have prescribed.

Only, in Bappi Lahiri, we did not just get an icon, but a superhero!

For this long haired short man flaunting the entire Kalyan Jewellers bridal collection, and then some, around his neck typified the spirit of the nation that we were to become, his capitalist-bull-in-a-socialist-china-shop personage breaking all the stereotypes that could have been. He embraced his obstinate confidence, he cradled his true blue rockstar credentials, he snuggled to his blings and glares, and in the process, he gave a big, big bear hug to us, to the India that was emerging. Highlighting that it was okay to believe in one’s supreme awesomeness, and that’s how any success story must begin. That we were no less than the others, that we were a strong, parallel force, complete with this luminescent luster that was both inside and outside of us, that even if we were questioned/ challenged/ ridiculed, we had reasons to be assured and optimistic, that we were ready to take on the world at our own terms.

Bappi Da’s public persona gave us the confidence to redefine cool, and create the idea of the lassi-in-a-can India that was blatant and unabashed and cheeky, ready to take off, and take on, and how! The man was Made in India much before aatmnirbhar became a part of our social lexicon. He gave us both coolth and comfort. And that’s essentially because he never tried too hard. The gold chains were naturally designed to be around him. The fancy sunglasses were mandatorily destined to cover his face. The self-comparison with some of the biggest international popstars was, therefore, the immediate and natural consequence. So what if he took inspirations ranging from Beethoven’s Fur Elise to UB40 to Modern Talking, he made them his own. He made them ours. This was him sticking it to the man, everything else be damned, and we loved it. The wheel, of course, turned a rather skewed full circle when he sued Dr. Dre for lifting one of his songs, Kaliyon Ka Chaman, and triumphed! We smiled. We chuckled. We laughed. We had arrived. We had won. The Kohinoor may still adorn the crown, we had managed our reparations.

Superhero. Bona fide superhero.

In my 10 years at MTV between 2000 and 2010, the decade that MTV was needed in India to shape and shake perceptions, Bappi Da and his personality consistently hovered around in our promos, shows, interstitials, powerpoints, the works. Hell, he literally hung out in all our acts and actions! But it wasn’t his musical presence that we are referring to. Newer sounds had emerged in both the mainstream Hindi film and Indipop spaces, and he did not really latch on to either. It was his radiant, care-a-damn presence, reflective, again, of the times we were living in. That assured rockstarness. The joie de vivre. He wasn’t willing to leave us. We weren’t willing to leave him.

I don’t think we would ever be willing to leave him.

Thank you for making us what we are, sir! Pyaar kabhi kam nahin karna.

The High Priest of the Lowbrow

Kader Khan wasn’t a writer or an actor.

Of course, IMDB credits him with some 110 titles as a writer, and 416 as an actor, and a career in Hindi films spanning four decades, starting from 1971. Op-ed pieces have reasons to sing paeans about his extremely prolific contribution to cinema, proudly propping up the impressive statistics of more than ten films a year on an average before or behind the cameras. His understanding of Hindi, Urdu, Hindustani and their apt everyday usage deservedly won him awards and accolades in equal measure. BUT. Kader Khan wasn’t a writer or an actor. Or just that.

Kader Khan was a concept. Kader Khan was a genre.

The 1980s were a decadent decade. Guess the sexy swag of the flower power was so very evolved and consuming and out-there, that it was kind of tough for the generation after to live up to its legacy. The existing icons were slipping, and the antithesis were getting deified. The spaces in Arts, Literature, Films and Fashion were being redefined, confusing the lows with the highs, and vice versa. Plastic defined the new aesthetics. Loud was the new doctrine. On the real world front, the bumbling buffoons of the Janata Party had mucked up the first non-Congress government and the bumbling buffoons of the country had decided to give Mrs. Gandhi a second chance. The angry young man was ceasing to be as angry. From the suave smugglers, the lalas and budmash bahus were making comebacks as the villains of peace. It was as if all the powers in the world had combined forces to put everything in the regressive mode. The pace had become slow. The bar had become low.

Enter Kader Khan. The high priest of the lowbrow.

Of his four professional decades, it was the 1980s that saw the Kader Khan phenomenon explode. He was involved in the story, screenplay and dialogues of more than seventy films between 1980 and 1989, and almost half of them were hits. From innumerous Jeetendra PT shows like Himmatwala, Justice Chaudhary, Haisiyat, Akalmand, Sarfarosh and Maqsad to the Anil Kapoor-Jackie Shroff bromances Andar Baahar and Karma, from Amitabh Bachchan megamovies like Lawaaris and Yaarana to family tearjerkers including Swarg Se Sundar and Bade Ghar Ki Beti featuring ungrateful sons and vicious daughters-in-law, to the exquisitely convoluted Khoon Bhari Maang featuring Rekha fighting a crocodile, Kader Khan helmed it all.

Here’s the thing, though. Kader Khan did not just create the 1980s cinema. He created the 1980s. He almost decided on the narrative for the decade. He established the world as he saw it. And the world became him. Where the hero could dance around matkas wearing atrocious wigs, sweaters and suits, taming the womenfolk who alternated between playing Thunder Thighs and Pyaar Ki Devi. Where Advocate Shobha and Meva Ram could co-exist with Naglingam Reddy, Desh Bahadur Gupta, Abdul Karim Kaliya and Pinto The Great Smuggler. It was a realm where he stuffed everything he could, and made it large.

The audiences lapped it up. They were indoctrinated already.

There was a method attached to the man’s mission, though. Kader Khan catered to the lowest common denominator without any apology. He was of the people, for the people, by the people, only, louder, shriller and definitely more piercing. The trick was to pick the right elements with the right connect from the world that surrounded him and enhance them manifold. That was the Kader Khan formula, if there was one.

His hero, therefore, was a potent and colorful mix of Chacha Chaudhary’s brains and Sabu’s brawn, complete with the native Amar Chitra Katha sanskaars, and a pair of dancing shoes. His character actors were garish, ear-splitting reflections of how he saw the real world. So the unscrupulous trader from Swarag Se Sundar (1986) isn’t just an unscrupulous trader. He is actually called Milavat Ram in case you miss his blatant beimaani, and his shop is called Do Aur Lo Karaane Waala, in case you still miss his blatant beimaani.

Kader Khan brought the lowbrow out of its cultural closet. Not only did he specialize in it, he basked in it. He genuinely loved the “ghun ki tarah gehun mein pisne waale gadhe” and did his darnedest to give them their place under the sun. His metaphors and similes were not to flaunt his linguistic wizardry. On the contrary, he browbeated them to such an extent that they ceased to be anything beyond this non-nuanced gimmickry of words. This democratization of upma and shlesh alankaars was poetic justice, so to say, for the masses. “Dosti ka thoda atta lete hain. Ussmein pyaar ka paani milaate hain. Phir goonth-te hain. Phir dil ke choolhe par rakh ke ussko pakaate hain.”, says Amitabh Bachchan in Yaarana (1981) while describing how he prepares rotis for his best friend Amjad Khan. Okay then.

He made moviemaking and movie-viewing a watered-down version of what they were, and he wasn’t sorry about it. Crass became mainstream, villains became comedians, comedians became circus clowns. When somebody points out to Mukri in Dharam Kanta (1982) how he is rather short to be a dacoit, he says, “Jab hum chhota daaka daalte hain toh hum chhote ho jaate hain, jab hum bada daaka daalte hain, hum bade ho jaate hain”. And then you sample this Kader Khan truism from Meri Aawaz Suno (1981): “Mera naam Topiwala hai. Maine bahut saare ghamandiyon ke sar kaat kar apne kadmon mein kuchle hain, aur unnki topiyon ko apne paas saja kar rakha hai.”, as you see Topiwala proudly displaying his prized scalps. You can’t get straighter than that now, can you?

The audience roared. Kader Khan worked. Full stop.

And Kader Khan continues to work. In Sambit Patra & Co. on news channels. In Bharat Mata Ki Jai Whatsapp forwards. In Tanishk Bagchi remixes. In The Kapil Sharma Show. In over the top characters and situations, dialogues laced with obtuse humor, vulgar misogyny, hahaha jokes and the dholak beats to highlight the punchlines. One may complain, get offended, feel repulsed, and rightly so. And then one may snigger when nobody’s watching. Because the lowbrow charm scores. Every single time.

“Mujhe swarg nahin jaana hai kyonki swarg jaane ke liye marna padta hai”, said Kader Khan in Ghar Sansar (1986) as Girdhari Lal.

Both Girdhari Lal and Kader Khan must be having a good laugh right now.

The unmaking of Chintan Upadhyay

The year was 1996. Mumbai was still a little bit of Bombay, the megapolis accepting us migrant cousins with open arms. Chintan Upadhyay and I were amongst the very many who had come to the city to make her our home. Mumbai was beautiful and affectionate, inspiring and challenging. The taller-than-tall apartments wowed us, the shimmering lights of the Crossroads mall and the display windows of Rupam and VAMA showrooms excited us. We were romancing with the local trains and rented homes in decrepit lower middle class societies, savouring our starvation in late night road side bhurji-pavs amidst the golden-brown haze of the sleeping city, revisiting our tangential dreams. And we knew we were growing up in an environment that we would romanticise about some day.

But I am digressing.

We were together at the Faculty of Fine Arts, the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda. We couldn’t take the isms and theories that we thought the world, the art world in particular, was drugged with. We wanted to create our own idiom, our own language, our own movement. We wanted to change the world. We were rebels without a pause, our shabby kurtasspearheading the mutiny. Baroda gave us the freedom to be. We revelled in it. Little had I ever imagined that Chintan’s freedom would be abruptly curtailed some day for what would look like an unlimited period of time.

But I am digressing again.

The Faculty taught us to think differently, humoring our attempts to create the revolution. Revolution of another kind was getting simultaneously created by one Dr. Manmohan Singh. The wise man sure was doing his bit to prod and perturb us lesser mortals. Liberalisation and Globalisation were ceasing to be mere buzz words. We could see the results in the hostel common room with MTV’s funky graphics staring at us, as we discovered a whole new universe, all bright and beautiful.

Before we could realize, we were in a strange, uncomfortable place. We could no longer figure who or what were we rebelling against. It was an odd conflict brewing in our hearts and our heads. This dispute wasn’t just between ideas and ideals. The fight was amongst our sanskaari past, our doordarshan-bred-hum-honge-kamyaab present and our shiny-disco-ball future. And it was a very very tough fight. Our middle-class idealism was being hit on its backside by this new India we did not know much about. But we realized we wanted to embrace this India. Despite the guilt.

The pride in poverty was stupid.

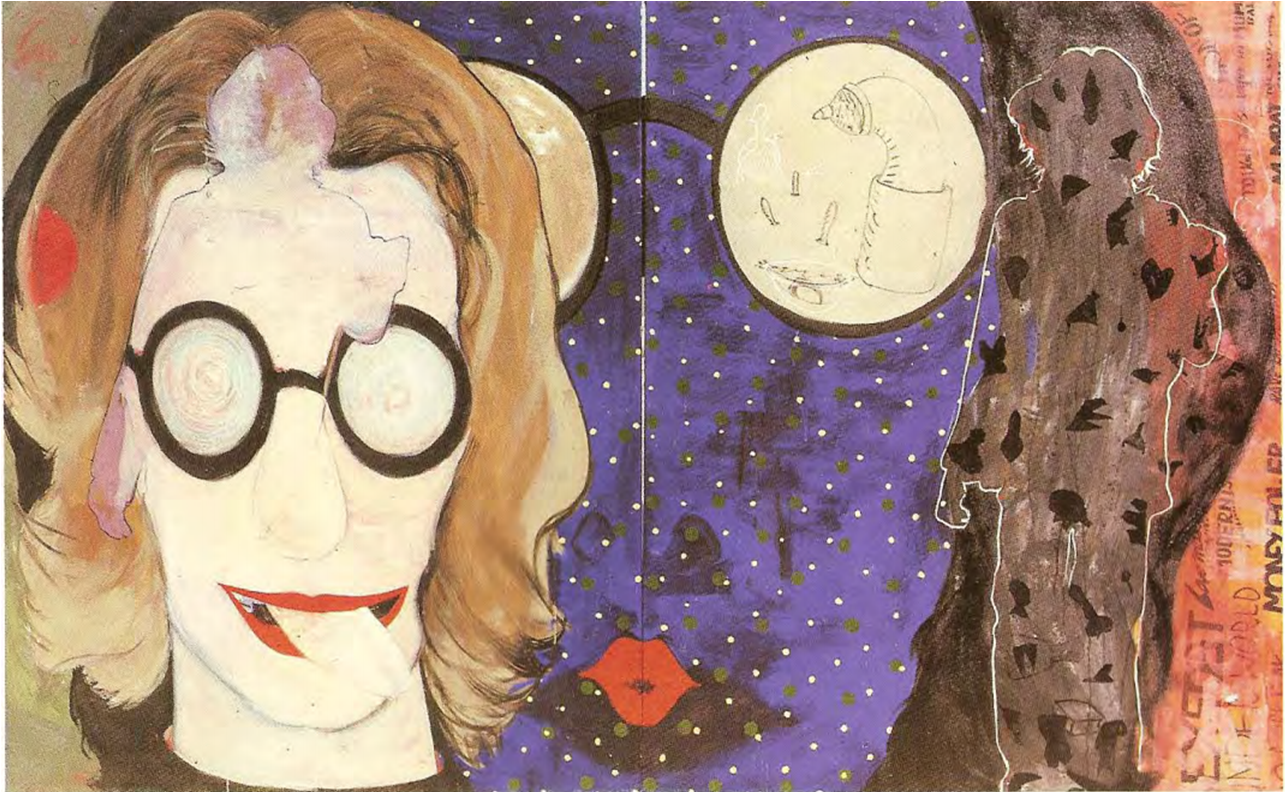

We were the gareeb consumerists, sold to the idea of consumerism, though not having the means to live it. It was during these days in Mumbai that I curated what was Chintan’s first independent exhibition. Titled This Has Been Done Before, the exhibition attempted to make a point against what we thought were the prejudiced norms, aesthetics and points of view in the world of Indian art. The catalogue was complete with a “Common Minimum Programme” for young artists. We had heated debates on what should the communication be. Chintan wanted to be loud and vociferous. I was recommending a more subdued approach. We ended up pompously calling Picasso and Gauguin ‘derivative artists’, and talked against the “biased and old fashioned attitude of the artists and art historians of the present century”.

This Has Been Done Before catalogue | 1998

This is how my piece began: “What, exactly, is Chintan Upadhyay? A frustrated phallicentric nerd out to prove the sexual connotations and escapades of everything surrounding him? Or a confused, overgrown kid, still in an animated awe of his trinkets and toys, but whispering voices of discontent against the system promoting their production? Is he just another faceless addition to a metropolis, coming to terms with the various layers of personae being gifted to him by the assemblage of cultures in a big city? Or is he simply an artist, sensitive to all things red, blue and green, exploring for an order in disorder despite his own sarcastic sneers against this search?”

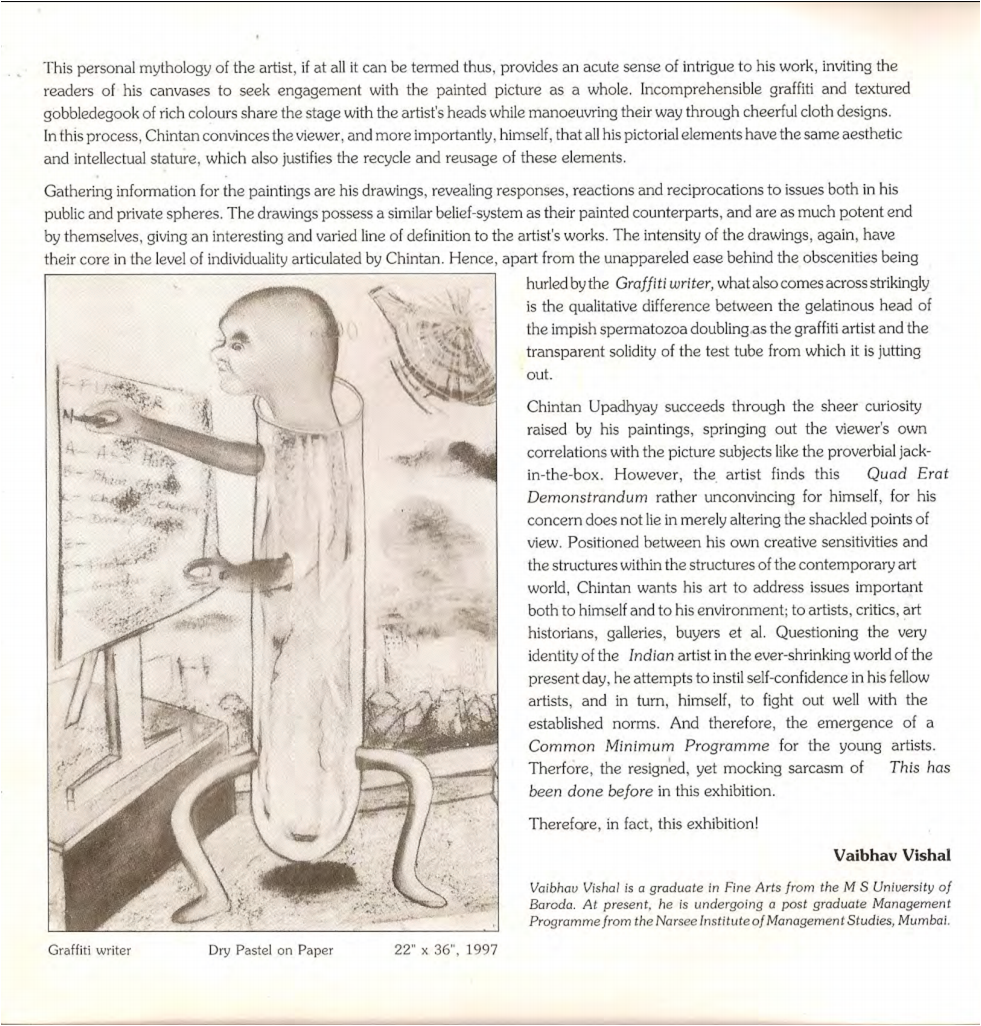

Multicultural face in a cosmopolitan city (Mumbai) | Acrylic on canvas | 10’ x 6’ | 1998

The exhibition was a failure.

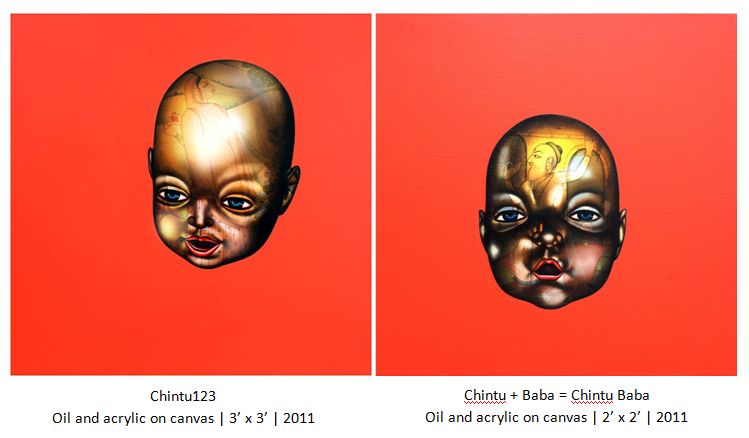

Not Chintan, though. He was sharp enough to figure that all the personas that I had spoken about had to be a subset of this overarching singular persona that he had to become. That’s how 90s was preparing us to face the new millennium. By becoming a brand new persona enveloping everything. The Common Minimum Programme was, therefore, out of his life. As were the thoughts of creating an artists’ collective. He had to get there first himself. He had to be in a space where he would be self explanatory and nobody would have to elaborate on “What is Chintan Upadhyay”. He latched on to the right people, allowing them to manufacture him. He figured the importance of marketing, of full page ads in Bombay Times pushing his works. Commemorative Stamps, his 2002 exhibition, flaunting the presence of filmstars and other pretty people at the opening, with wines and cheese we never knew existed, and a completely new artistic language, was a super hit.

A brand was born.

There was no looking back after that. Chintan was always the talented one. He knew it in time that it was not about being just an artist. It was about being a popular and successful artist. The kind that sells. What followed was how most of us 1990s kids embraced the changing times. We figured that life wasn’t about brooding and snorting our middle class affiliations. It was about breaking patterns. It was about earning and spending and earning some more to spend some more. The conflict that was, soon ceased to be. It had been dissolved and resolved.

Chintan, of course, went beyond that. In the quest to become a consumerist, he became a heavily marketed consumable product himself over the next ten years. We continued to play conscience keepers to each other, although I now suspect our chats, infrequent and few, were more to flaunt and justify our acts and actions than question them. I don’t know how convinced I was of the transformation of the Multicultural face in a cosmopolitan city to the mass produced Chintu, and also those performance art sessions created to shock and awe, but I guess he knew what he was doing. Chintan and Hema – another friend from the Faculty of Fine Arts – became the ‘it couple’ of the Mumbai art scene. His ganda bachchas were all over. She was kicking some serious ass as an artist of repute in biennales and triennales across the globe. Chintan’s compromises – artistic and otherwise – were worth the heartburn. He had become famous. He had arrived. He had become one with Mumbai.

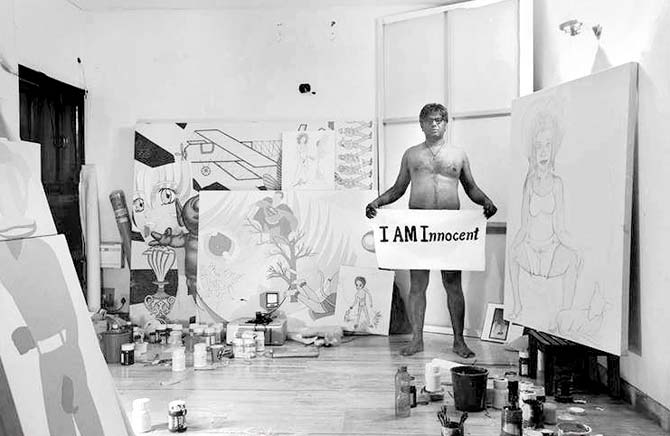

But then again, success and fame have their own trappings. The couple learnt it the hard way. After some very petty fights and a very public spat over their divorce proceedings, their love story came to a tragic and abrupt end. Post their formal separation, Chintan started work afresh, low key and guarded. And then, suddenly, Hema was murdered. What followed was a macabre prime time drama that then turned into a tragedy. Insinuations, charges and counter charges. Cops playing art critics, reading motives in his doodles and diary entries. A man in jail since 22nd December 2015, held as a suspect in the double murder of the ex-wife and her lawyer. Guilty until proven innocent. And a trial that is still in progress with witnesses yet to be examined, and the supposed killer still at large. Almost seventy months of confinement. Six long years of waiting.

The honourable Supreme Court finally granted bail to Chintan on 17th September, 2021. Amongst other things, the Court has instructed him to reside in any place other than Mumbai, and visit the city only for the purpose of attending court. They have banished him from the city that made him into what he is now!

But I am not going to give this a Shakespearean hue, and project Chintan as the tragic hero. Despite knowing his journey from 1992 to 2021. The prolonged and tedious trek that he took from the Borivali shanty to the Juhu house, and then to the courtrooms and the Thane Jail, redefining his art and himself in the process. Almost thirty-odd years, how it all panned out, how our values, successes and failures got defined and redefined. I know of his hopes and desires, fears and apprehensions. I know he is very many things, or that he became very many things that I think he was not. I also know that his struggle was real, the achievements hard-earned. I would not want to believe that he would squander it all away just to cater to his whim or vindictiveness. I know his truth. I hope for the world to know it, too.

I am innocent (I hope you know why) | Performance art | 2013

I also hope he come out of this more insightful a person. With the same set of hopes, aspirations and positivity that was there when we came to Mumbai in 1996. I may ask him to go back to the Common Minimum Programme when we meet up. He owes me a chai and a long conversation. About what we were and what we became.

We shall curse the 90s. We shall bless the 90s.

(First published in Midday, Mumbai)

Ranting on rice, and then some

Of all the stupid things that the Indian humans can do to showcase their ‘talent’, writing on rice grains sits right at the slimy, slushy bottom of the universe, not very far from creating gulab jamun vadapavs, or getting 8-year olds to do pelvic thrusts on national TV because dance India, dance.

Unless your brain has been designed to sexualise Ajay Devgn’s gutka-painted teeth, how can you even think that writing microscopic letters on food grains can be a good idea! I mean, why. You have all the time and patience in the world. You can crack the nuclear codes. You can write your own philosophy. Hell, you can start your own cult.

But. No.

You take a grain of rice. You scribble something on it. You then realise it cannot be read by the naked eye. This is when you must stop. Instead, you get inspired to doodle some more. And then some more. Till you write the entire Bhagavad Gita on grains of rice. Grains that could have been rightfully converted into biryanis, dosas, kheers or phirnis, and justified their presence on the planet. Only, you decide to convert them into freakshows for Uncle Barnum’s circus. Painted with the kind of precision and perfection that can make great serial killers on a good day.

And your fellow countrymen offer milk to your Ganesha statue seeing those tiny mutated pebbles. The lines between crafts, arts and gimmicks blur till they become a huge blob of nothingness. The middle class almirahs filled with middle class aesthetics go ballistic showcasing these granular inanities. Along with milk art, paper carvings, drawing on sesame seeds, and ugly large dolls in their original packaging, of course.

Gulab jamun vadapav and a grand salute to you! Kya baat. Kya baat. Kya baat.

It’s mucky at the abyss for everybody, Kangana!

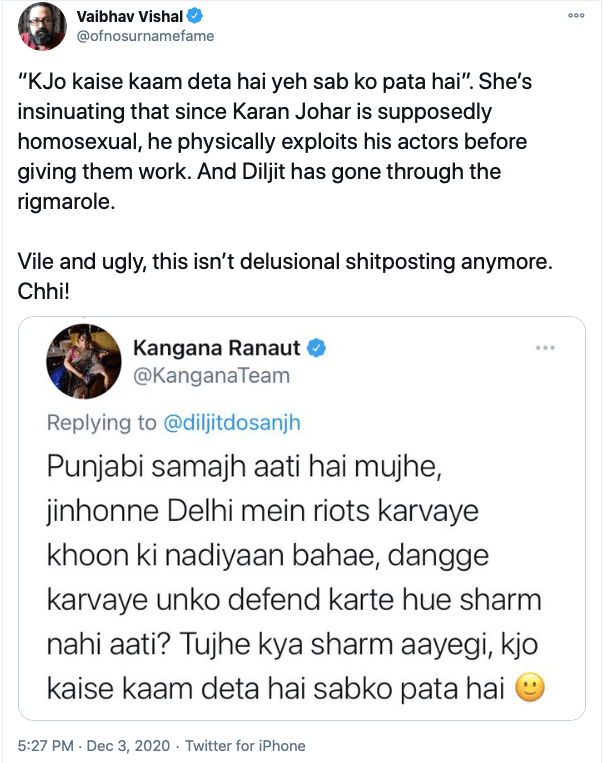

So. This tweet went viral yesterday.

I had a point of view on what Kangana had said. Her biases were showing. And I maintain that she was being extremely vile and ugly by getting Karan Johar in a completely unrelated fight, making snide remark on his sexuality, and insinuating that Diljit Dosanjh must have done something with Karan to get a role in a Karan Johar film. Or whatever. That was a really, really low blow, even by Kangana’s depleting standards. She went on to give a lousy counter-point, saying she had meant something else and the filth was in the mind of the readers, but the excuse/ explanation was so flimsy that it vaporised by the time it left her keyboard.

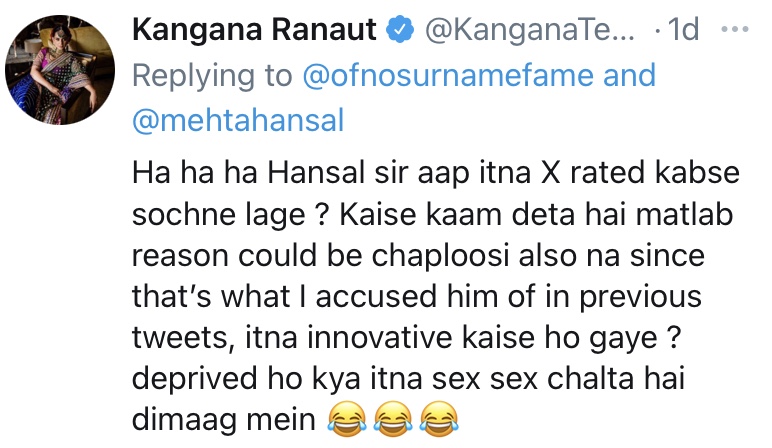

This was Kangana’s response to Hansal Mehta’s RT of my tweet.

I don’t care about Kangana’s politics. She can be a rabid right winger or apolitical or a liberal left winger. It is well within her rights to be what she wants to be, and be loud about it. It is also well within her rights to question/ troll/ fight with whoever she thinks isn’t on her side. I get it. The Kangana-Diljit debate in isolation is what makes us such a vibrant democracy. People with differing ideologies can exist simultaneously. Along with the mid-roaders. Debates, even in the form of passionate fights, are important for any democracy to flourish.

Only, there is a decorum that one expects in debates, be it in the Parliament or State Assemblies or on a public platform like Twitter. If you are a public figure, and people look up to you, then you have even more reasons to stay in the dignified space. I am fairly certain even Kangana has a point of view on the chairs, mics and chappals being thrown by the Lawmakers on each other. Her remarks of personal nature were equivalent of that rowdy chair throwing. Kangana lost the debate when the insinuations began!

However, this is not about Kangana.

What has bothered me more is the overwhelmingly large number of tweets and replies supporting what I have said, but doing PRECISELY what I have a problem with. So thank you for your replies and quote tweets, but you are NOT on my side. And I don’t need you on my side with your pronounced hatred and grating misogyny. For you are being no different from Kangana when you are questioning how she got her roles or what she did to Mahesh Bhatt to get her debut film. You are being exactly her when you are calling her a prostitute, dhandhebaaz, randi, and what have you. Hell, you are being worse when you are posting pictures from her movies, characters that she has played in fictional narratives, and are using those to question her character!

I am sorry, but you can take your pathetic prejudices and your inherent sexism and shove it where there is no sunshine! This is for each one of you, Kangana included.

I may disagree with Kangana, and I do, I may also find her approach towards her confrontations repugnant and cannibalistic, but that cannot be the reason for me to call her names. Or vice versa. This is where we do not want the discourse to go. Because once we reach the abyss, it will be mucky for everybody. We would all gasp for breath, and there would be no way to reach the surface ever. I am sure Kangana would agree with this some day, and have a debate the old fashioned way, with arguments and counter-arguments.

I will buy her a chai, agree to disagree, and fight to win. :)