I’m leaving on a jet plane to Canada, and money is not an issue

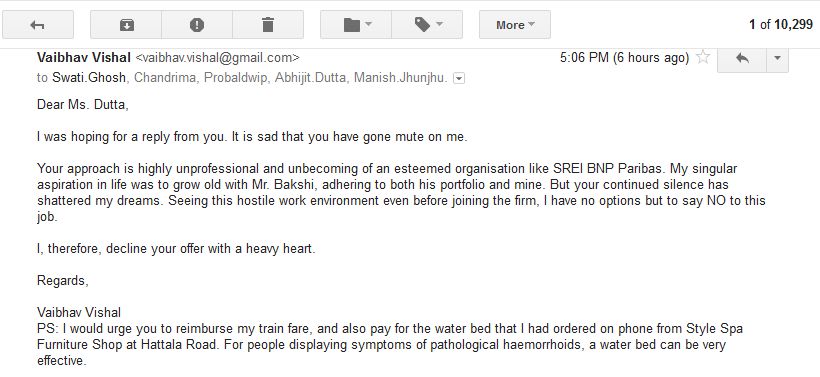

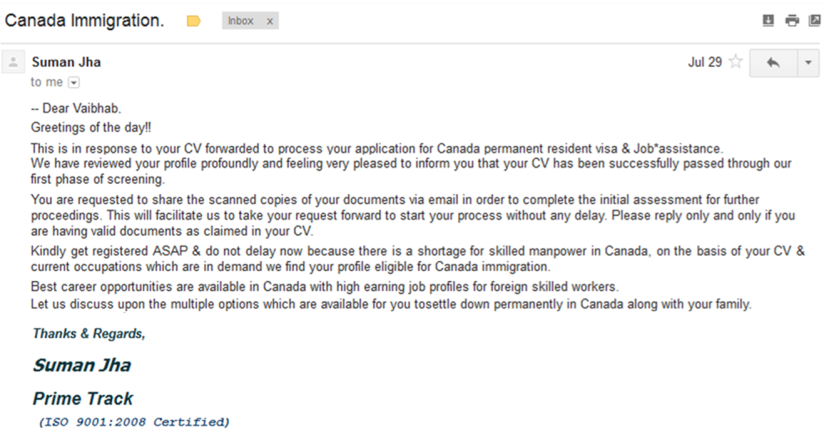

I am a big fan of Justin Trudoeu Tredaeu Treduae Trudeau. I like Canada. I like Canadians. I also like Punjabi, the language most of the Canadians speak. So, naturally, I was intrigued when I got a mail with the subject “Canada Immigration” from one Suman Jha from Prime Track, an ISO 9001:2008 certified firm specialising in sending people to far out countries. Fairly articulate and persuasive, our man informed me that there was a shortage of skilled manpower in Canada, and the time was right for me to start the process of migrating to Canada without any delay. He also told me that he had profoundly reviewed my profile and that he was very pleased to inform me that my CV had successfully passed through what I am assuming must be their rather stringent first phase of screening process.

This was all fantastic. Only, there was one very minor technical issue. I had not sent him my CV.

So I did what any self respecting man secure with the belief that the best career opportunities were available in Canada with high earning job profiles for foreign skilled workers would do. I ignored his mail.

However, the eloquent Mr. Jha, with his dogged determination and stubborn seduction, would not have taken no for an answer. He sent a few more mails over the next four weeks, reminding me of the interest I had shown, asking me for the details of my documents, and promising me the completion of my documentation under the fast-track services. This was all too good to be true, this outpouring of concern and affection. Unfortunately, random unnecessary work took over my life, and I could not write back to him. Let’s just say the admiree was very much aware of the admirer’s strong overtures, but I had to consciously reject it.

Suman continued to have my best interests in his mind. The natural extension of his love was yet another mail from him.

“It;s a golden opportunity”, he said.

That one sentence did the trick. Guess I was hit somewhere deep inside – the semicolon hitting the colon, as they say – and that was enough to shake me out of my complacence. I was charmed and charged by the radiance of the golden opportunity, ready to immediately take on his offer. I was raring to go. And Canada was waiting.

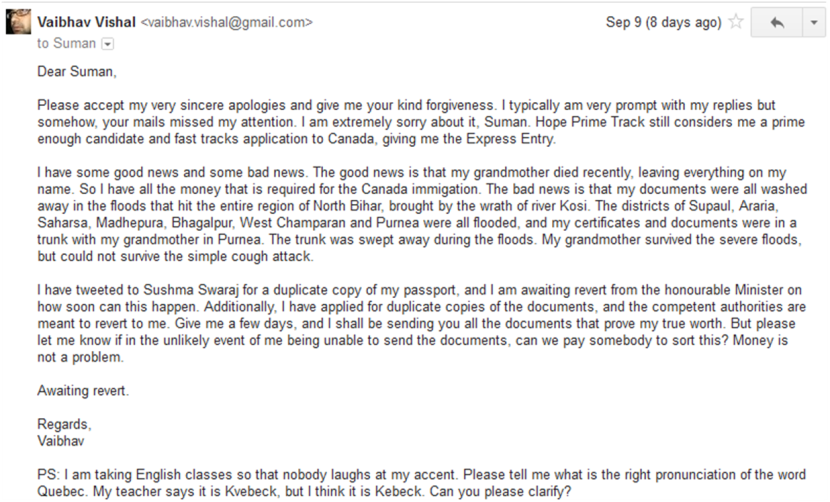

I wrote a polite response explaining my silence and my readiness, in order. The mail also outlined some very regular practical issues I was facing. But I was sure it was nothing Mr. Jha or Prime Track, an ISO 9001:2008 certified firm, would not have been able to sort.

Surprisingly, my positivity was reciprocated by a very stoic silence. It was as if the fizz had gone from our relationship. It was my turn to follow up.

The professional Mr. Jha had a single-lined response for me. Apt. I deserved it.

He had not asked to me for write my biography. Obviously. I was blinded by the warmth that I had seen, and it had led to some weak moments. He was totally right in chiding me. This is exactly how businesses are conducted. I realised my mistake and apologised profusely to the man who stood between the Rocky Mountains and me.

Sassy Suman was back in the game. He sent me a quick reply asking me for my CV and other documents.

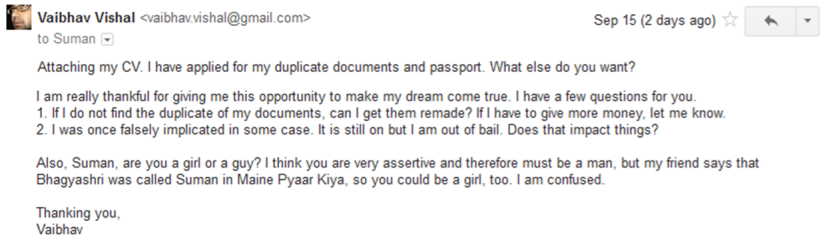

By now I had figured the curt Mr. Jha meant business. I sent my biodata to him almost immediately. I also had some basic queries for him to address. Felt stupid and sorry about sending those inane questions to him, thinking how smart guys like him have to go through such dumb Qs in their line of work. But then I thought Mr. Jha and Prime Track, an ISO 9001:2008 certified firm, must be used to such harmless naiveté of their clients.

He rejected my CV.

Crestfallen, I wrote a rather poignant mail to him. I was hurting. And it didn’t feel good. But despite the grief and the hurt, I maintained my poise and my positivity. I felt like a Himesh Reshammiya heroine. With a smile on my face and a song on my lips, I asked him to reconsider my application.

His response was the complete anti-thesis of the turmoil going in the atriums of my heart. He started using his silence to numb me, and comfortably so. I waited. Twenty-four hours later, I decided to graciously confront him while respecting his point of view.

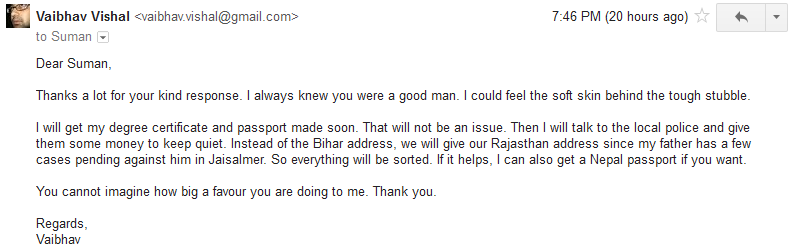

I knew he would come around. I have lots of money. And come around he did.

THIS was the point where I figured a thing or two about the psychological make of Mr. Jha. He was a man of few words. That’s what he wanted in a man. He didn’t want long treatises. He wanted short jabs. I had to change my strategy to stay ahead in the game. I had to become as succinct as him.

The whole world stood in silence as the mano-a-mano struggle ensued between the two protagonists. And then he spoke. I had nothing but gratitude towards the big man.

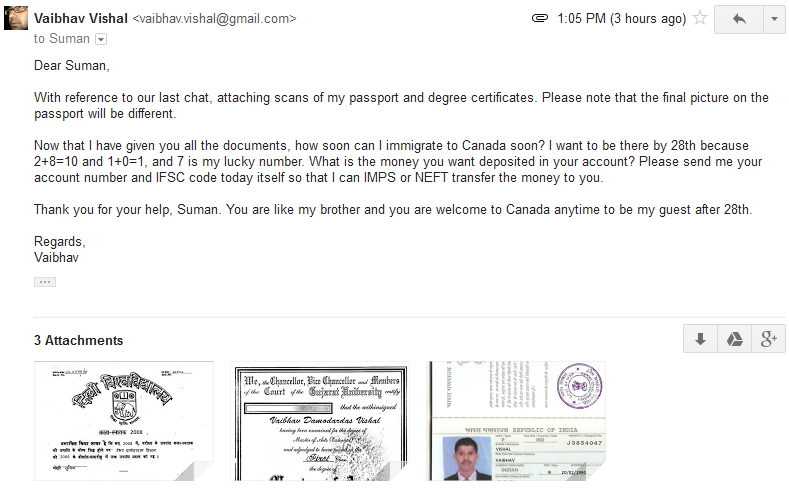

Soon enough, I sent him all the documents that were needed. He had given me this extreme resolve to fight, live and survive. The underlying tension had led to this overarching tenacity. I was ready to take on the world!

I knew what I was talking.

(And here are the scans of my passport and the BA degree. All legit, of course.)

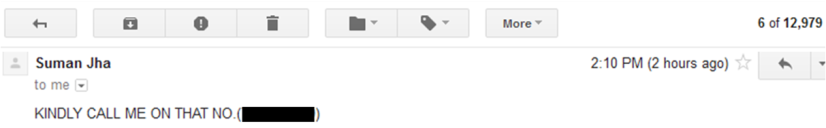

It worked. We were now willing to go to the next level. We were exchanging numbers. And I am not just talking account numbers here.

This was not just a mail exchange I was having with the man. This was a life lesson I was learning. We were talking the talk. Kind of.

Just after I hit “send”, I realised that I had ended up sharing some very critical information about myself. And I knew it instantly that it would come back to harm and haunt me.

I had inadvertently revealed that there was somebody else in my life.

Mr. Jha decided we were done. He knew he had to severe all ties with me at one go. Just like that. Or not.

:|

He closed my file, but he opened my life. I am upset, yes, but at the same time, I am content that this experience made me find answers to that one question that has always bothered the mankind.

“Had i asked to you for write your biography?”

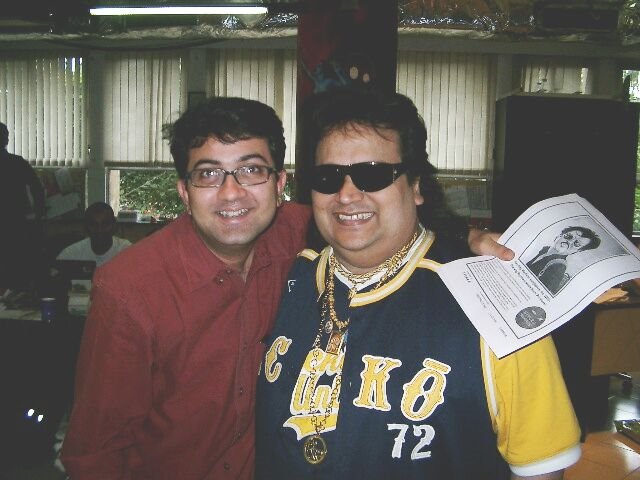

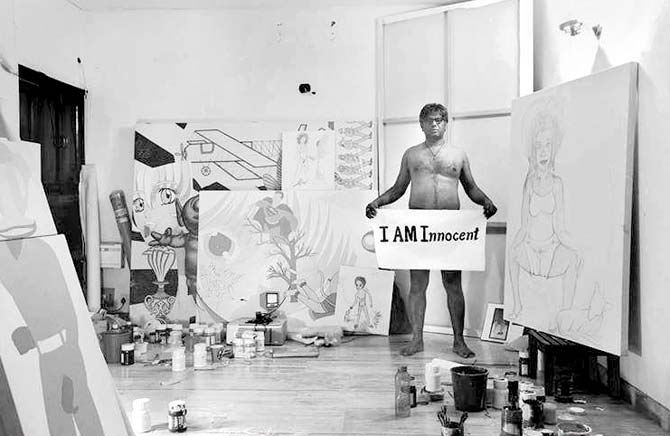

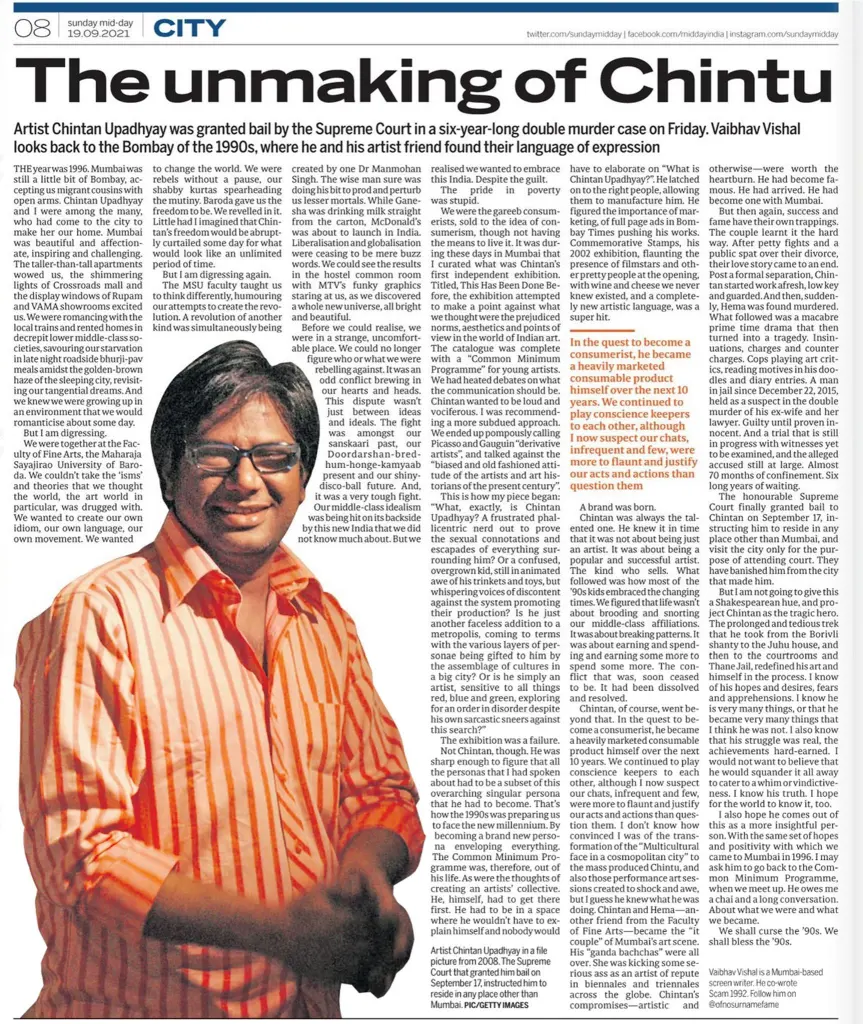

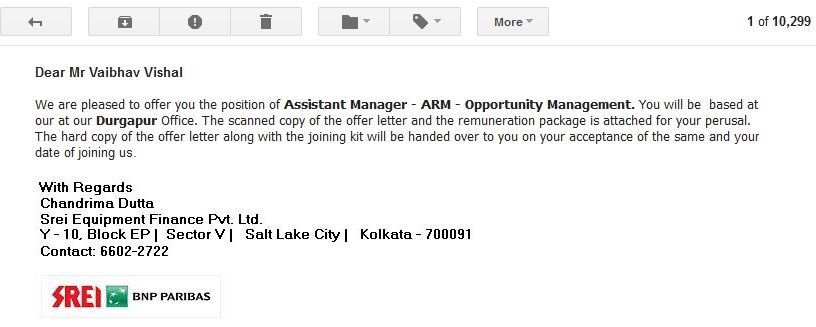

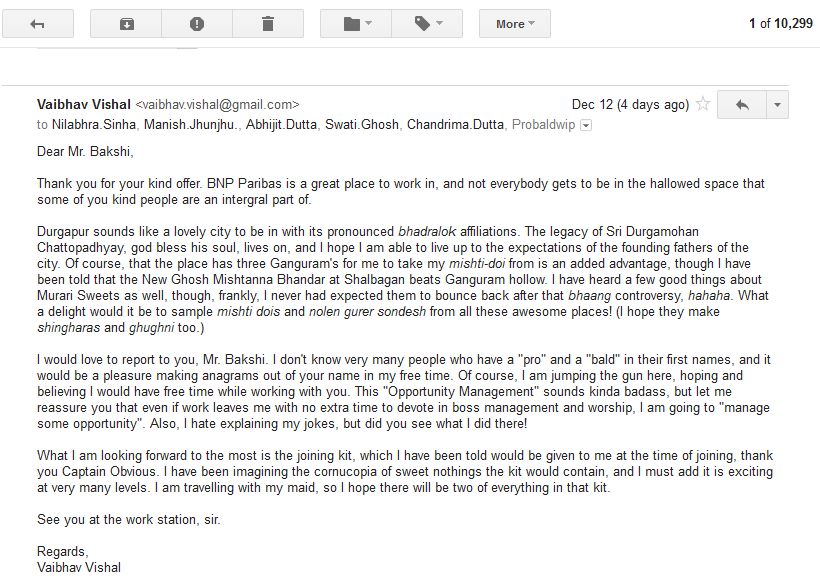

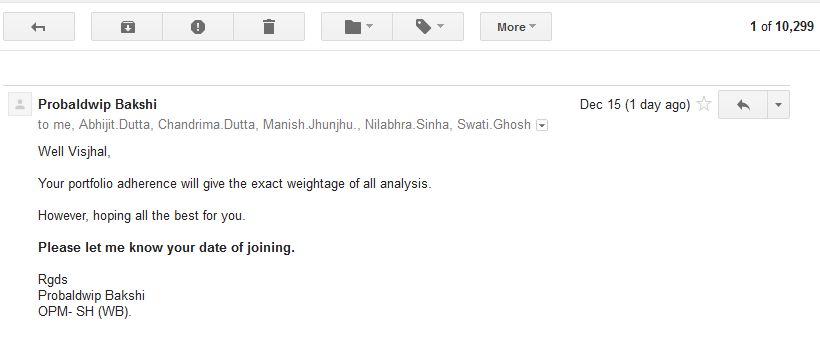

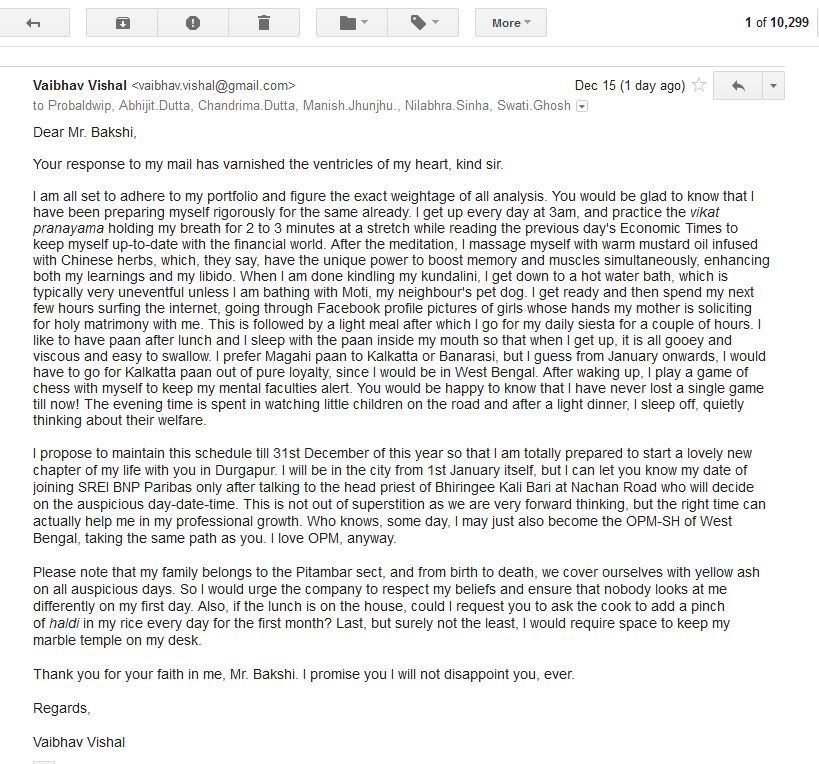

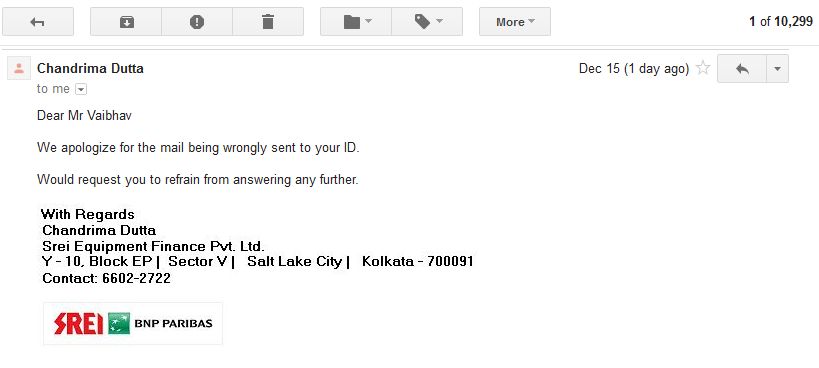

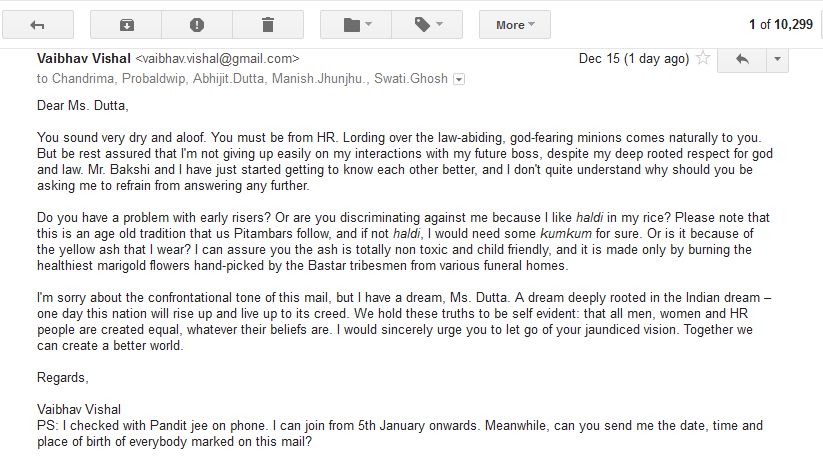

(If Close Encounters with Suman Jha is your kind of a thing, you may want to know more about my original heartbreaker, Probaldwip Bakshi.)