Category: Notes

The Gods Must Be Trashy

Posting something I had written for my FB group “I Love Trashy Hindi Movies”. Have made a few minor factual changes without disturbing the flow of the article.

If it reads a bit dated, it is. :)

***

Understanding the exact factors leading to the kind of socio-political-cultural change the TV serial Ramayan could bring into the Indian subcontinent has always been a rather baffling experience for me. Despite my best efforts, I have never been able to crack how on earth could the Maganlal Dresswaala foreground and the rapturously revolting Ravindra Jain background catch the fancy of so very many viewers across the country. Seriously – and this is where it gains significance in our forum – Ramayan, at best, was B-grade cinema in a pukishly pretty mythological avatar, with a rather cracked conglomeration of lousy actors, lousy sets, lousy costumes, lousy wigs, lousy masks, lousy special effects and lousy everything else.

Compared to Ramayan, the other lethal mix of Punjabi-Bollywod aesthetics and Gujarati-Bollywood imagery, Mahabharat, was a shade better in terms of production values. But even this BR Chopra creation finds its rather important place under the sun in our space, essentially because of the wealth of actors it could contribute to the cause of B-grade cinema. Gajendra Chauhan, Girija Shankar, Pankaj Dheer, Nazneen, Arjun, Puneet Issar, Mukesh Khanna … quite a few of these guys actually stemmed from the abyss and then went back again to where they belonged immediately after the serial got over.

Okay, before some of you decide to burn me, my laptop and my computer table (and mob-lynch a few gareebs, while you are at it), this is not meant to be a comment on the epics. It is the sheer shoddiness of these serials, and the scars that that they have left, that I am commenting on, specifically talking about their actors.

Arun Govil: Post Sawan Ko Aane Do and Saanch Ko Aanch Nahin, all Mr. Govil saw was the downward path till that effeminate wig in Vikram aur Betal helped him resurrect himself. Who would have thunk that a 30+ failed actor of repute would make a rather grand re-entry as Maryada Purushottam Ram, straight out of a high school musical, obtuse hair-do, beedi strained teeth, plastic smile et al. He was a phenomenon while it lasted. After Ramayan, Govil and his hired dhotis made paid appearances in Ram Lilas across the country till Adwani took over his role. And that’s the last we heard of him.

.

Deepika Chikhalia: Ekta Kapoor used to be a regular girl growing up on Mills & Boon, playing hopscotch. Till she watched Deepika aka Seeta in action, that is. And that’s where she found the prototype of Tulsi, Parvati and what have you, all rolled into one. Ms. Chikhalia went on to do two bit roles in a few movies opposite Rajesh Khanna (this was in the bloated-rectangular-face phase of RK’s life; the bearded-dried-tomato look followed later) and also became a respected Member of Parliament. Yeah, that’s the same place where Hema Malini and Dharmendra also go once in a while. Uggh.

.

Sunil Lahri: From bhaiyya Ram to bhaiyya Kishan… Bhaiyya Kishan Kumar, that is! If somebody could do a two bit role in a two bit actor’s debut film (the reference, of course, is to Aaja Meri Jaan) then that man must surely be out of job. I rest my case.

.

.

Sanjay Jog: He was the non-smoking brother of Ram. Jog did impress in his character of Bharat, but his career could not move beyond Jigarwaala or Naseebwaala. Till his unfortunate departure. He would have found employment in any of the BATA showrooms. Nobody took care of footwear as he did, seriously.

.

.

Vijay Arora: Vijay Arora sang Chura Liya to Zeenie baby. And then he played the lead in Nagin aur Suhagin. And then he widened his eyes and landed up as Meghnad, looking like Karunanidhi without his glares, speaking Hindi in Punjabi. Arora’s rapist-in-a-dhoti look did not find any takers following the epic, and though he did do ten odd movies subsequently, his career graph could never go further north.

.

Padma Khanna: Talking of actors from Ramayan, special mention to Padma Khanna aka Kaekayi. Guru Suleiman Chela Pehelwan, Ghunghru ki Awaaz, Sultana Daku, Kasam Durga Ki… Padma Khanna was destined to do B-grade Hindi films, though she did end up doing a not so bad job in whatever better movies she could act in.

.

Dara Singh: And, of course, there was Dara Singh, the king of the B-bling. Nalayak. Boxer. Lutera. King Kong. Raaka. Badshah. Hercules. Samson. Faulad. Rustam-e-Baghdad. Jagga Daku. Sherdil. Khakaan. Tufaan. And this on-screen Hanuman also could also romance with Mumtaz in the movies! Now if only he had not produced Vindu, his life would have been perfect.

.

Before I move to actors from that other epic Mahabharat, let me reiterate that my list is not at all comprehensive. I have missed quite a few gems. I would put the blame squarely on Jambwant, yet another of those Ramayan characters, for hitting my brains. If you are not familiar with him, imagine a fat man with hair all over him. Then imagine the same man constipated for 10 continuous days and despite all the sat isabgols of the world, unable to get it out. Now imagine the same man attempting to utter “Shree Ram”. Yeah, that was Jambwant. And yeah, thanks for sympathizing .

Mukesh Khanna: Naam – Bheeshm Pitamah. Baap ka naam – Deenanath Chauhan. That sums up our man in Mahabharat. Khanna moved on to become the quintessential Thakur/ policeman across various movies, progressing from Jaidev Singh to Suraj Pratap Singh to Shakti Singh to Mangal Singh to Thakur Raghuveer Singh to Khushwant Singh to Thakur Harnam Singh to Rana Mahendra Pratap Garewal to Rai Bahadur Mahendra Pratap Singh. Btw, those were real names of the characters he has played, no kidding! Meanwhile, he also produced, directed and acted in this brilliantly tacky TV serial called Shaktiman, which has helped a whole load of unintelligent lower middle class kids stay the same all their lives.

.

Girija Shankar: No blind man can look as lecherous as Dhritrashtra looked in Mahabharat, simultaneously eyeing Gandhari, Kunti, Draupadi and all the hired straight-out-of-a-dandia-night extras with his kaat-loonga looks which only Girija Shankar could produce. Amongst his 15 unforgettable movies subsequent to Mahabharat, I would give special mention to Divine Lovers (produced and directed by B. Subhash of Tarzan fame), where he plays this Indian guru cum psychologist cum psychiatrist cum doctor called Dr. Pran! Please watch this movie to witness Bappi da’s English songs, Mark Zuber’s claws, some quality soft porn action (Don’t judge me. I was in college then.) and Hemant Birje’s bare butt (Don’t judge me. Even if I was in college then.).

.

Dharmesh Tiwari: Tiwari played Kripacharya in Mahabharat. Then he acted in Aurat Aurat Aurat. His claim to fame, though, is that he reunited the entire Mahabharat team in his directorial debut called Mahabharat aur Barbareek. Gaudy, garish and gory, it was the stuff the rainbow tinted mythological orgasms are made of. It was India’s Expendables, only they really were. The movie tanked. Obviously.

.

.

Pankaj Dheer: From Mera Suhag to playing Karna in Mahabharat and then to the Zee Horror Show, Dheer’s filmography could have been more impressive had he got the right breaks. Pity, because he could act better than lots of the other guys.

.

.

Gajendra Chauhan: Gajendra as Yudhishtir could display a whole plethora of emotions in the show. Sample this.

The poignant: (nasal twang) “Mumble, mumble, mumble, mata shri!”

The brave: (nasal twang) “Mumble, mumble, mumble, bhrata shri!”

The sensitive: (nasal twang) “Mumble, mumble, mumble, Panchali!”

The decisive: (nasal twang) “Mumble, mumble, mumble, Duryodhan!”

Yeah, he was quite an actor, this guy. Which explains why Salman beats him up in Baghban. Yeah. And then, of course, they made him the Chairman of the Film Institute of India. Because why not!

.

Roopa Ganguli: Krishna saved her in Mahabharat. Wish he was also around to save her from Bahaar Aane Tak, Inspector Dhanush and Meena Bazaar. Good actor, though. She has done a few quality Bangla films, making up for all the movies she did in Hindi.

.

.

Puneet Issar: A blur of massive chest hair is all what I remember of Puneet Issar from the show. Of course, he had already proven his talent in Purana Mandir, Saamri, Zalzala and Zinda Laash before he cracked the role of Duryodhan. Guess he had done enough of sari pulling already. After Mahabharat, Khooni Murda and Roti ki Keemat were enough indicators of Issar’s superb body of work. And if that does not impress you, unravel this man through his directorial debut Garv: Pride and Honor.

.

Arjun/ Feroze Khan: He was quite the hero of Mahabharat. And with actors like Praveen Kumar and Gajendra Chauhan playing his brothers, he did not have to work extra hard for that, either. Unfortunately for him, he did not find any takers in the film industry, and was reduced to playing the comic villain sidekick in films after films. He also had a two bit role in Karan Arjun. Irony, hit me on the face again.

.

Nitish Bharadwaj: He who perfected the art of smiling with his lips sealed and the art of nodding with his head unmoved, Nitish won quite a few admirers for his performance as Krishna. The charm did not last beyond the great war. A few insipid movies like Trishagni, Naache Nagin Gali Gali and Sangeet later, he was back in his Krishna avatar, only this time asking for votes for BJP. As of now, he wears Made-in-Ludhiana pullovers and still does the same.

To come to their defense, the tragedy of most of the religious stars is that their screen image becomes so very imposing that the audience just refuses to accept them in form of any other character. Despite the roaring mega-success of Jai Santoshi Ma, Anita Guha could not do anything significant, EVER. This, precisely, is the reason why most of the religious actors’ careers, including the ones discussed – and this definitely is not a comprehensive list – have taken such sharp nosedives after their initial success. Unless, of course, they have been saved by Kanti Shah and his producer brethren.

Thank god for that! ;-)

PS: If you liked reading this, you may also be okay with Why Gajendra Chauhan is the greatest FTII Chairman EVER!

I got a job offer from BNP Paribas. What happened next would not shock you!

I rarely get mails which offer me jobs. In fact, I rarely get mails. Solitary reaper, et al. Which explains why I got so enamored and impacted by this mail forwarded to me by one Probaldwip Bakshi from SREI BNP Paribas, offering me a job as “Assistant Manager – ARM – Opportunity Management” at Durgapur. The mail was accompanied by the scanned copy of the offer letter and the renumeration package. For my perusal. (I didn’t really have to write the last sentence, but I don’t always get to use the word “perusal”, and I think I have a secret crush on the word. So yeah. For my perusal.) I was also told that the hard copy of the offer letter along with the joining kit would be handed over to me on the day I would join them.

Now, I have always had a fixation for joining kits. I rarely get joining kits. Plus, “Assistant Manager – ARM – Opportunity Management” sounded like my kind of thing. But most importantly, who can say no to working with Probaldwip Bakshi! Naturally, I lapped it all up, and sent a merry reply confirming my acceptance.

Mr. Bakshi, the OPM – SH (WB), sent me a short and curt reply, establishing the working relationship and expectations. That’s the kind of boss I have always wanted. Quick on the uptake and sort of British. Succinct and successful. I could only thank my gods for the good fortune. More so, because I rarely get replies.

I sent an immediate mail back to Mr. Bakshi, offering him my undying support in this momentous journey we were about to take together. I also had a few routine questions and clarifications pertaining to the job.

I sent an immediate mail back to Mr. Bakshi, offering him my undying support in this momentous journey we were about to take together. I also had a few routine questions and clarifications pertaining to the job.

And just when I had started thinking how I would play Tonto to this amazing Lone Ranger, I got a note from Chandrima Dutta, asking me to stop all communication on this subject. Just like that. No, really!

Crestfallen and dejected, I tried figuring this sudden change of behavior towards me. We were on a happy Paribas ride not very long time back, all of us, and now this! My innocent mind could not fathom why would something so bitter and brutal reach my inbox. And while I have always followed the peaceful path displayed by Dr. Martin Luther King, I could not control myself from questioning the logic behind Ms. Dutta’s mail.

Crestfallen and dejected, I tried figuring this sudden change of behavior towards me. We were on a happy Paribas ride not very long time back, all of us, and now this! My innocent mind could not fathom why would something so bitter and brutal reach my inbox. And while I have always followed the peaceful path displayed by Dr. Martin Luther King, I could not control myself from questioning the logic behind Ms. Dutta’s mail.

Ah, Human Resource people, why art thee so cold, callous and cruel! Not only did Ms. Dutta decide to not write back to me and answer my good-natured, noble-intentioned questions, she also used her continued silence as her strongest weapon to shut me up and crush my child-like enthusiasm. This painful placidity, this sullen stoicism was too much to take for the very emotional me. My plan to make a difference to the world was savagely sabotaged by the world.

Ah, Human Resource people, why art thee so cold, callous and cruel! Not only did Ms. Dutta decide to not write back to me and answer my good-natured, noble-intentioned questions, she also used her continued silence as her strongest weapon to shut me up and crush my child-like enthusiasm. This painful placidity, this sullen stoicism was too much to take for the very emotional me. My plan to make a difference to the world was savagely sabotaged by the world.

I decided to not take up the job. :|

This hasn’t quite been the best experience of my life, but I still believe in the goodness of mankind. I believe in angels, something good in everything I see. I believe in quoting from an ABBA song and not giving them any credit for the same. I believe in honest people getting what they deserve, what is rightfully theirs.

Only, I rarely get mails which offer me jobs. :(

(I later gathered that the email ID of the guy they were trying to write to was vaibhav.vshl@****.com. Clearly, his favorite actor is Ajay Dvgn. His Action Jackson affiliations notwithstanding, I’m sure he makes a better candidate than me, and would do very well at the awesome organisation that SREI BNP Paribas is, blending in with the lovely people in there. All’s well that ends well.)

The answer is Munna Aziz. Always.

You need to understand the 1980s to understand the impact of Mohammad Aziz on the 1980s. It was quite a decade, it was. When glitz was plastic, and glamour was gaudy, and the flamboyant and the convoluted walked hand-in-hand. We were in a zone hitherto unseen on the cultural front – read films, fashion, art and literature – and we were rather proud of where we were going without really knowing where we were going. This was the decade when Pomeranians were the rich dogs, cordless phones outlined one’s social standing, Rupa and Dora were best-selling national brands of men’s underwear, and Halla Gulla Mazaa Hai Jawaani defined young people who wore headbands and paid to watch Karan Shah in Jawaani (1984).

It was the baroquest Baroque that India could ever have been.

Men wore baggy trousers and thought they were the shizz. Women wore plastic jewelry and thought they were the shizz. Hindi film villains were called Dang and Mogambo, and they thought they were the shizz. They were right, of course. Columns of earthen pots painted for the Gay Pride Parade formed the backdrop of dancing ditties featuring heroines wearing conical cholis. Heroes contorted muscles that weren’t even discovered by Science or the human body. Rekha and Jayaprada, our reigning divas, looked like the Klingon warriors from Star Trek. And everybody else looked like Rekha and Jayaprada. Including Amitabh Bachchan, Jitendra and Mithun Chakraborty. Hamming was acting was hamming. They all signed up for the classes.

This coincided with the coming-into-being of Mohammad Aziz, famously known as Munna Aziz, or vice versa, in the world of Hindi Cinema. He arrived on a tanga with Amitabh Bachchan, no less, and, stayed on to simultaneously collaborate with the slushy histrionics of actors including Dilip Kumar, Amitabh Bachchan, Rajesh Khanna, Dharmendra, Mithun Chakraborty, Rishi Kapoor, Anil Kapoor, Sanjay Dutt and Govinda with equal ease, and enhanced élan. The voice had just the right amount of ornate density that was the crying need of the hour. The motto of the decade was Expression Without Suppression, and Aziz was meant to be one its biggest, happiest, breeziest votaries. With Mard (1985), Karma (1986), Khudgarz (1987), Pyaar Ka Mandir (1988), Ram Lakhan (1989), Tridev (1989), and then some, he clearly was at the right place at the right time. The hummable, hammable hits were an immediate corollary. From the flashy rhythms of Aapke Aa Jaane Se to the simpering patriotism of Har Karam Apna Karenge, from the excited revelry of One Two Ka Four to the loud proclamation of Main Teri Mohabbat Mein, Mohammad Aziz reflected all that made the 1980s.

Hell, Mohammad Aziz WAS the 1980s!

Aziz entered the Hindi film music scene when there was a rather visible interval of sorts. Mohammad Rafi had just passed away and Kishore Kumar’s presence was being kind of selective. Older singers like Mahendra Kapoor, Talat Mehmood, Manna De or Mukesh were either gone or fading away. The Nadeem Shravan factory featuring Sanu and Sonu was still to happen. Udit Narayan’s Papa was yet to proclaim bada naam karega for his beta. SP Balasubrahmanyam was a glorious glint only in the Madrasi mothers’ eyes. The producers, directors and music directors had reasons to believe that the best alternative to the voice of Rafi was the voice of Rafi. Therefore, Anwar, Shabbir Kumar, Mohammad Aziz and Sonu Nigam chronologically filled in, matching Rafi husk for husk.

But Mohammad Aziz wasn’t a first-copy version of Mohammad Rafi. That would be playing unfair to the artist that he was. Mohammad Aziz was the first-copy version of all the actors that he sang for. He was Govinda’s pelvic thrust, Mithun Chakraborty’s swagger, Shashi Kapoor’s gravitas, Rajesh Khanna’s ham, Amitabh Bachchan’s buffoonery and Dilip Kumar’s melodrama. He was all that they were or wanted to be.

Imagine Rishi Kapoor and his sweaters singing Tune Bechain Itna Ziada Kiya to Sridevi in a single-screen theatre. The setting is right. The trees are around to be danced around. The lehngas are having a cheerful dalliance with the chunnis. There is enough mohabbat-majboor-vaada-iraada in the song to make the coronary arteries give warm cuddles to each other. It’s a love ballad. Only, with Mohammad Aziz, it becomes a loud and proud pronouncement of Rishi Kapoor‘s feelings for Sridevi. To such an extent that it continues to hit you long after you have left the theatre. It stays with you. Forever.

True. Story.

And this is because Mohammad Aziz’s voice was invented for single screen theatres. Be it the urban centers exhibiting state-of-art sound system or mofussil towns making do with their decrepit speakers, if it is Aziz that they played, he would be heard. Whatever be the quality of audio systems, it could not shake or rattle him. Why, even if there were no speakers, you could hear Mohammad Aziz!

But to know the real impact of the man, all that you had to do was travel in a video coach in the 1980s Hindi-speaking India. The worn-out video tapes may get the visuals wrong, they may skip scenes, they may even stop moving, but they would never ever EVER screw around with an Aziz song. The rickety buses all over the country were not running on diesel. They were running on Munna Aziz.

Because Munna Aziz was a concept. A phenomenon.

His presence signified the emergence of the lesser India. From “Beta aunty ko Chooby Chiks suna do”, it now was “Beta, Rafi uncle ko copy karo”. He legitimized the hopes and aspirations of the middle-brow-middle-class India. He was Munna. He was one of them. One of us. That an orchestra singer could actually become part of the mainstream was the Revenge of the Also-Rans. Mohammad Aziz was the biggest tribute to the orchestra culture of India. The orchestra culture of India was the biggest tribute to Mohammad Aziz. They were the fall-out of each other.

Precisely why when his time was up, he went back to where he belonged. To the orchestras. Where ill-fitting black suits with purple ties and fancy glares made for fancy people on stage. Where misogynistic jokes on co-singers made for great content. Where the singers actually thought they were the actors that they sang for, performing for an audience that actually believed in it. The middle India continued to love him back.

To be one of the cultural symbols of a decade that was culturally so decadent must have not come easy to Aziz. Which explains the quick rise and fall of not just Aziz, but all such symbols. Exactly why we need to give them their deserving place under the sun. Mohammad Aziz must never be on the lost pages of History, or be relegated to merely becoming an apologetic footnote. Because he was an integral part of the history when it was being created. His personal documentation of the times he lived in through the songs he sang is pure and unadulterated, even if it does not match with our evolved sensibilities and heightened sensitivities. “Kaun hai woh. Bolo bolo kaun hai woh. Haan bolo bolo kaun hai woh”, he famously asked in Jaane Do Jaane Do Mujhe Jaana Hai from Shahenshan (1988).

The answer is Munna Aziz. Always.

Chhatth Puja and the GulshanKumarisation of India

My Bihari cousin is getting married to a lovely Tamilian girl.

I am sure the dainty Miss Sridhar must be doing her homework already to know more about what she is getting into. We may not have life sized cut-outs of Ms. Cloaked Rotundity and Mr. Goggled Baldness, but we have enough loud fodder loud enough to make her feel at home. What we lack in flashy flamboyance, we make up with our brassy brashness. We are a raucous country, yes ma’am. When the alphabets were getting distributed, the Biharis decided to take everything with all the hard consonants. Marathis come a close second. Pethe, Kekade and Madke would agree.

But let’s stay on Bihar. Or in Bihar, if I were to take Raj T’s advice.

So we have Litti, Laktho, Thekua, Ghughni, Bhabhri, Makuni, Khaja, Pedakiya, Gaja, Dalpittha as a smattering of names randomly taken from the Bihari fridge. NONE of them sound appetizing. Not one. They taste phenomenal, but they don’t sound like something you may want to consume. And some of them look like what they sound like.

Blame it on the pastoral background of the Biharis, if we were to get all historical and sleuthy. While the neighbourhood Bengal was busy carving intricate creases on their Nolen Gurer Sandesh, singing their Baul and doing their Dhunuchi Naach, Biharis were too busy either tilling their lands or rearing Chanakyas, Buddhas and Mahaveers. So they did not really have the time to create artworks in the kitchen or outside of it. We developed as an ungainly and unsophisticated nation, without any apology and with a definite hint of pride. Take it, world!

And this gets reflected in everything we do. Or say. Or make. Or celebrate.

Which brings me to Chhatth, a festival that some theorists claim even predates the Vedas. At the concept level, it has perhaps the most modern outlook for a festival so ancient. There is no idol worship at all in Chhatth, unlike most Hindu festivals. It is not gender or caste specific. And there is no involvement of a presiding pandit. No random mumbo jumbo being babbled by some patronizing priest working on an hourly remuneration in front of a gaudy concoction of gods. It is a festival with rituals led by the devotee, dedicated to the deity. A hardcore one-on-one with the all-encompassing to acknowledge and achieve the common, combined greater good.

Spread over four days, the worship is dedicated to the Sun god and his wife Usha, greeting and thanking them for creating and controlling all the life forms on the planet earth. While Chhatth follows Diwali, it is no selfish agrarian festival stemming from the contribution of sun to the agricultural produce, coinciding with the cultivation. It is a very noble recognition of the influence of sun in our combined lives, way beyond its material beneficence, with pronounced philosophical undertones. Which explains why the worship of the rising sun is preceded by the veneration of the setting sun.

So far, so good.

Only, I don’t remember getting influenced or enamoured by any of this while celebrating Chhatth in the Patna of the late 1980s. Neither by the philosophy behind the festival, nor by its rather liberal stance. Outside of the exhilarating thrill of traveling at 4 in the AM for the morning arghya, moving past the colourfully lit-up roads to a crowded Pehelwaan Ghaat or Collectorate Ghaat, and then letting the feet play with the cold, moist sand, what actually has stayed with me is the harsh aesthetics of it all.

I am not referring to the festival, of course.

I remember the crowd. A sea of humanity amidst all the muck of the riverfronts. People rushing at the ghaats with their chaadars, fighting for and marking their territories to be as near the slushy expanse of the Holi Ganga. The rich and the powerful moving around with their gun-toting musclemen. The blaring loudspeakers, the long traffic jams, the arguments on the roads, the hawkers selling posters of Hindu gods, including Arnold Schwarzenegger, and the general wide-ranging cacophony of the people forming a buzzing backdrop. It all came together into something memorably lurid and raw.

This rasping rhapsody was amplified by the sindoors on the noses of the parbaitins, or the fasting worshipping ladies. Indeed. A shining, flaming, thick and radiant saffron vermillion marking starting from the tip of the nose meandering into the parting of the hair. Imagine multitudes of ladies with their brightly painted noses half immersed in the muddy waters, offering their obeisance to the rising sun. The effect was mesmerizing. The effect was daunting.

To be fair, though, it was not just these nose antennas that were browbeating me into meek submission to all things colourful and coarse. The GulshanKumarization of India had just about started to happen. The combined might of jhankaar beats recorded in cheap Darya Ganj studios on Super Cassettes was beginning to juice the entire pantheon of Hindu gods and goddesses. Johnny ka Dil Tujhpe Aaya Julie was being appropriated as Bhakton Ka Dil Tujhpe Aaya Devi, and then some. People not only seemed okay with these, they were, in fact, revelling in them. It was a crude, uncouth phase in the life of India, both culturally and otherwise. Patal Bhairavi and Bhavani Junction were legit Hindi cinema releases, Rajeev Kapoor was playing the Lover Boy, Rajesh Khanna was romancing Reena Roy, and people were really paying to see Raj Babbar on the large screen.

It was the attack of the lowbrow. And Chhatth was as impacted as any other festival.

So in the middle of the folk songs evoking the Sun god, the shrieking loudspeakers would play one of them Karolbagh ditties sung by Babla and Kanchan. Hum Na Jaibe Sasur Ghar Re Baba. Yeah. Soon enough, these tardy renditions were accepted as a part of the mainstream. The eighties never left the festival. The festival never left the eighties. Every subsequent Chhatth was more of the same. Exciting. Rousing. Breath-taking. And very bloody loud.

I moved on. Bombay became home. Then I shifted to Mumbai.

Patna, Bihar and Chhatth continued to be a part of my subconscious persona, but not being there meant not being there. My new native city gave me newer references to ponder over. I had graduated from Gai Ghaat to Lal Bagh. I had moved on. Or so did I think. Untill I suddenly discovered the luminous vermillion-nose brigade in a traffic jam at Juhu one fine evening. The parbaitins were back in my life, and how! And I was amazed to see that twenty-five years later, the unhinged aesthetics and revelry were unaffected, give or take a few Sanjay Nirupams trying to make Chhatth the North India Pride Parade. It was beautiful. To be in that jam. To be back there. To relive the scale and the noise. And to revisit the fantastic reasons behind the celebration of this wonderful festival.

Here’s to many such discoveries, Sanjana! And welcome to the family. Some of your new relatives may look like aliens once every year, and their vocabulary may be predominated by words with ट, ठ, ड and ढ in them, but we are good, warm god-fearing people, I promise you. Despite that fluorescent patch on our noses. Or because of it. :)

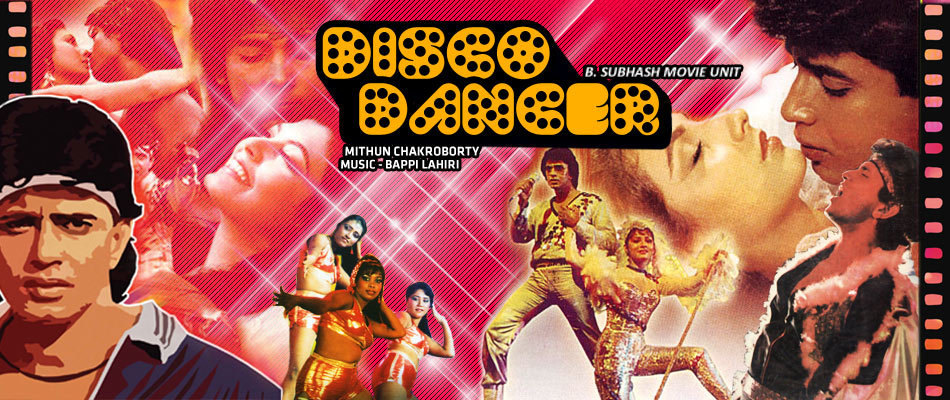

It was quite the time to Disco!

The last quarter of 1982 was extremely exciting in the history of India primarily for two reasons. The Asian Games came back to New Delhi after a gap of three decades. We realised that we were capable of rising above mediocrity as a nation and make our mark as a progressive and progressing country. Confident landmarks like Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium, Indraprastha Indoor Stadium and Khel Gaon got added to the Mughal-Lutyen landscape of the capital city, and became a part of the collective national modernisation dream almost overnight. We understood the power and impact of live TV, with the athletic pixels beaming across the country through seedha prasaran on Doordarshan. Offering solidarity to the cause, the TV screens started transforming from black & white to coloured, showcasing the buoyant hues of the tricolor like never before. Ath Swagatam Shubh Swagatam, we sang on 19th November at the Opening Ceremony, welcoming and celebrating the world and India, and I also suspect, the first mega-public appearance of Amitabh Bachchan after the Coolie accident.

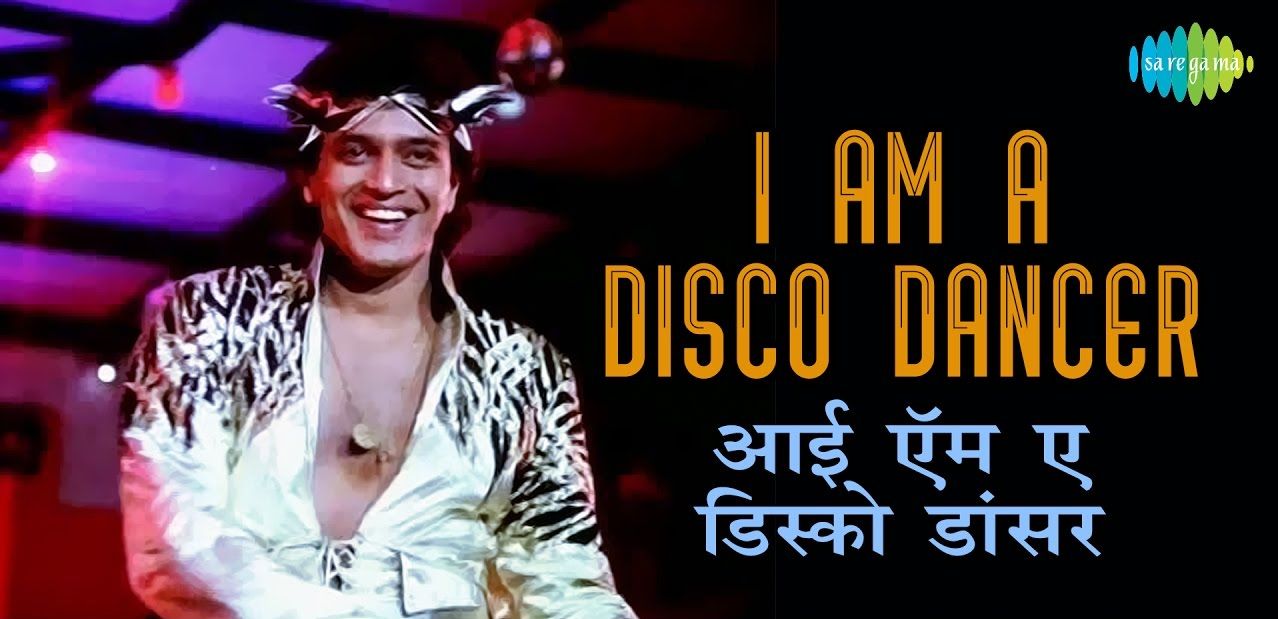

The other big event in the life of India was the release of Disco Dancer.

B Subhash’s Disco Dancer is the rags to riches story of Jimmy (Mithun Chakraborty playing Mithun Chakraborty) who braves acute poverty to become India’s best disco dancer. Fighting the whims and fancies of his punishing fate and inner demons, Jimmy goes on to ace the coveted International Disco Competition, bringing joy, pride and honour to the nation and her people, one pelvic thrust at a time.

There is enough in Jimmy’s stimulating and sterling biography to shake, rattle and roll the viewers. As a kid, he is falsely accused of stealing by PN Oberoi, the evil rich businessman. His mother takes the blame and goes to jail. The mother-child combine is taunted and tormented with the cries of maa-chor-beta-chor (which, for the record, does not sound like what it is meant to sound like), and they leave Mumbai to settle in Goa. Jimmy grows up to sing and dance at local weddings, while Oberoi’s son Sam becomes the country’s most popular disco dancer, and a pompous ass with ill-fitting moustache and trousers. His manager David Brown leaves him because of his wayward ways, discovers Jimmy, and soon enough, Sam is dethroned. Side note: Om Puri playing a character called David Brown is why a lot people from the 1980s still have trust issues.

The now-famous Jimmy exposes Oberoi at a party, and also falls in love with his daughter. Outblinged and outsmarted, Oberoi gets his men to electrocute Jimmy through his guitar, but kills his mother instead. Jimmy gets Guitarphobia, developing cold feet at the Competition, unable to dance. That’s when Rajesh Khanna in a career defining special appearance as Raju Bhaiyya hams what looks like an entire episode of Kyonki Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu Thi to motivate Jimmy, asking him to “Gaaaaa!”. The film is still called Disco Dancer. “GAAAAA!”, he beseeches and screeches. Jimmy gets his mojo. Oberoi’s goons kill Raju Bhaiyya to make him ham some more. Our hero kills them back. Oberoi gets electrocuted.

And they all lived happily ever after, thank you, Dr. Rahi Masoom Reza and Deepak Balraj Vij for the multicoloured glitter in your pen!

This may sound very simplistic and formulaic, thanks to my ha-ha-ha retrospective gaze, but for the 1980s cine-goers, nothing could be farther from the truth. Disco Dancer is not a film. It is a state of mind. This journey of the lowbrow to the high street is an electrifying – in more ways than one – celebration of the absurd and the awe-inspiring, the real and the surreal, the sounds and the silence. Disco Dancer is definitely not a film. It is the overwhelmingly viscous space between the trash and the transcendental.

The audiences, while rooting for the classic good-versus-bad tale, also played cheerleaders to what they thought was the emerging, new India. Where the macho hero could be a dancer, wear shiny clothes on stage and lungis at home, shake his limbs without any love-interest around for most part of the film, be surrounded by fangirls, and still have his mother feed him food with her own hand. This was a protagonist hitherto unseen. Not a brawny rebel, but an artiste, a performer. Who could fail and clam up and cry, but finally emerge victorious. Because maa ka aashirvaad. That a primarily western and alien concept like disco could be mainstreamized, with quintessentially Indian storytelling and a central character that never would exist in real life is what got the audiences to the theatres. Then you had the emotions, struggles, failure, success, vengeance, love and drama. Also, Jesus Christ and Krishna. Plus, a mandatory Rahim Chacha, thank you.

Disco dancing became us.

While there was not much to talk about the country’s economy, militancy was rearing its head in Punjab, mills in Mumbai were coming to a standstill, and the honourable Prime Minister was publicly throwing out her widowed daughter in law from her home, we were still dancing. Maruti Suzuki was on the threshold of giving the middle-class-middle-brow India wheels that they had never imagined, Amitabh Bachchan was gearing himself to get back to the studios after a long stay at the hospitals, Chambal dacoits had started wilfully surrendering, Kaur Singh and Satpal were trouncing their opponents at the Asian Games in Boxing and Wrestling respectively, Jimmy was crushing the disco kings and queens from Afreeka and Paris. Things were beginning to look up. Toh jhoomo, toh naacho, aao mere saath naacho gaao. We had reasons to believe. Backed by Bappi Lahiri’s music. And moustachioed men wearing ballerina dresses complete with tutus.

The Buggles may claim that Radio Killed the Video Star, but Auva Auva belonged to Bappi Lahiri and Usha Uthup. Jesus by Tielman Brothers could become the ballad of Krishna, and Jesus did not really mind it seeing the perfect fit. The ultimate winner of the film, though, was the title song, I’m A Disco Dancer. The song starts with Mithun jumping on the stage, and then freezes on a screaming woman’s face for almost 5 seconds. That, in a nutshell, sums up the impact of the film on its audiences. Hypnotic and frenzied. It wasn’t as if Mithun Chakraborty’s histrionics or Bappi Lahiri’s music had any novelty value. Ravikant Nagaich had previously gifted Surakksha, Sahhas and Wardaat to the audiences. But Disco Dancer turned out special because of its very universal, very identifiable theme. The synthetic saga of tribulations and triumphs scored because of its straightforward simplism. And not just in India. It was the first Indian film to pocket 100 crores worldwide, with Goron Ki Na Kaalon Ki becoming an unlikely anthem across countries!

The impact of Disco Dancer was pretty much like the Asian Games. It made us feel all good and gooey till the next big jamboree. The beats were lost to the Madrasi eyesores featuring Jeetendra, and then to the Nadeem Shravan onslaught. Mithun went on to do Ooty films. The buzz around Kaur Sing and Satpal was forgotten already.

But what a thrilling high it was when it lasted! It was quite the time to disco.

(first published on Arré)

Amitabh Bachchan and I want you to read this!

So the Outlook magazine invited me to attend its first ever Outlook Social Media Awards. Abbreviated to perfection as OSM Awards, sweetly echoing the millennials’ propensity for all things abstracted, these awards are meant to honour the best in social media. I don’t really know what I was doing as a jury member among the likes of Shashi Tharoor, Prasoon Joshi, Shilpa Shetty, Ritu Beri, and many such prominent, newsprint-smelling names who routinely remind me of my lowly existence.

But then again, every Bigg Boss house needs a commoner. I was just the right man, come to think of it. Plus, to be fair, I suppose I do know my social media. I can outrage about everything without knowing anything. The astute observers of the magazine had recognised this ability, figured I had the right amount of frivolity and triviality, and invited me.

The night was quite a glitzy affair, as one would expect any such night and any such affair in the national capital to be. There were luminaries galore both on and off stage. The newsmakers and the news disseminators, political bigwigs, business leaders, bureaucrats, filmstars, TV actors, social media megastars, Page 3 people, and a smattering of expats… the aces and the faces all dressed to precision, reflecting the fragrant dazzle of the sophisticated night.

And then there was me. Over-bearded. Overweight. Overbearing.

The very kind, very compassionate (and very blind, I suspect) people of Outlook chose to ignore all that. It was like my shaadi.com profile had briefed them on my virtues. I was soon getting ushered in and being led towards my row and seat amid all the blinding lights and fanfare music.

They made me sit right behind Amitabh Bachchan. The. Amitabh. Bachchan.

Nobody ever makes me sit behind Amitabh Bachchan. Or if they do, there is a gap of a hundred rows or a hundred miles, whichever is more, between his coiffured hair follicles and me. I was sure something was amiss. I checked the name tag on my chair. It said SECURITY.

Now, I take my all-caps very seriously. If you are talking to me in capital letters, say hello to the meek, subservient me. Naturally, I looked around to see if I had usurped the rightful place of, say, an AK-47-bearing black cat commando. Didn’t find anybody looking at me intently with feelings of any kind in upper-case and the people behind me were getting edgy and annoyed. So I had no other option but to perch myself at a place that did not belong to me.

I sat. Behind Amitabh Bachchan. The. Amitabh. Bachchan.

The thing about sitting behind Amitabh Bachchan is that people are looking at you. Constantly. At the event, and later on television. Lots of people are looking at you. And not with love. Everybody who is looking at you thinks and believes you are a jerk. That you don’t really deserve to sit behind the man. You don’t deserve to be there, jerk. You got lucky, jerk. You are a jerk, JERK! This is true for anybody who sits behind Amitabh Bachchan. By default, that person becomes a jerk, even if he were a double Nobel prize winner. Only Amitabh Bachchan can afford to sit behind Amitabh Bachchan and not be called a jerk by the world.

The other thing about sitting behind Amitabh Bachchan is that, well, you are sitting behind Amitabh Bachchan. You are seeing the back of his head, and the side of the side of his face. He is not really turning around to say hi to you. He would never do that. He knows you are a jerk.

So you change angles. Casually. You bend forward. You move rightward. You move leftward. You bend backward. Delicately. You stretch and contort your body to get a better angle. And you fight this intense, uncontrollable urge to grow your neck and use it to hoist your face in front of the man. Because that’s exactly what you want to do. You are excited. You are breathing heavily to capture all the carbon dioxide emitted by him. But at the same time, you don’t want to show any of it. But a part of you really wants to make an event out of the situation. But you take it easy because you are kind of cool like that. AND you hate being in the situation that you are in. More so, because no matter howmuchever hard you are concentrating and trying all those spells you learnt from Harry Potter or the imageries you picked up from Tom & Jerry, you are unable to grow your neck.

I sat there with a stoic expression. Fighting envious eyes and my own inner impulses. Like a true warrior. It’s all cool, people. I do this for a living. Yeah. I uttered this to myself, realising I had suddenly developed an accent. Which was the point when Shashi Tharoor on stage posed a question for Amitabh Bachchan. I don’t remember what the question was. I don’t remember what he answered.

All that I now remember is that, suddenly, some thirty-odd photographers with flash-lights of various intensities emerged out of nowhere, pointing their cameras at Amitabh Bachchan and me.

Okay, then.

This was a really, really tricky one. If I stayed all detached and impassive, I would look arrogant or, worse, disoriented. If I looked at the cameras with all enthusiasm, matching my expressions with Amitabh Bachchan’s intonations, I would appear wannabe or worse, an ass-kisser. The last option was to look the other way, but thank god, I am not that big an idiot. Ergo, I did the best I could. I tried what I think is my enigmatic Buddha smile. The sort of smile that the photographers can never blur out of an image, even if they were to obliterate the background. I looked at the camera people with all earnestness. If the baritone needed a back-up, here was the thing to capture.

We were becoming a team, Amitabh Bachchan and I.

He was soon called on stage to give away some award, and I clapped the loudest. Knowing I was being watched. I was now playing his cheerleader, manager, confidante, and mentor all rolled into one already. And I sure was loving and living it. This was my moment.

I looked at him getting up, and bestowed him with the patronising hansi-khushi-kar-do-vida thumbs up. I also benevolently decided at that very instant that I would never tap his shoulder and ask him to put his head down if he sits in front of me at some theatre. I would also let him keep his seat-back reclined even if he and I were on 21A and 22A respectively on an IndiGo Airlines flight. This was becoming a permanent fixture in my life, me sitting behind Amitabh Bachchan. Quite a picture I was painting. The claps went into slow motion, the sounds became fainter, while my eyebrows continued giving a quiet and glowing tribute to Akshaye Khanna.

He came down. He walked past me. He left. Just when I was getting used to the idea.

I looked at the pictures from the event the next day. The photographers at the Outlook Social Media Awards had managed to cut some or the other part of my anatomy from all the pics. Clearly, they hated me. It was almost personal. Meanwhile, Amitabh Bachchan was looking like the superstar that he is. I was looking like the Before version of a Sat Isabgol model in those before-and-after ads for laxatives. It was depressing.

My mother saw the photos, too. Her reaction: “Oh, woh tumhare saamne Amitabh Bachchan hain?” Kaboom!

Me: 1. Amitabh Bachchan: 0.

(First published on Arré)

When Vinod Khanna asked for doodh and killed a hero!

The first time that I remember seeing Vinod Khanna on the big screen was in Qurbani at Vaishali Cinema in Patna in 1981. The story of the film is a blur now, but outside of the sexed out Zeenat Aman’s Aap Jaisa Koi and Laila O Laila, what still stays with me is Amjad Khan’s sass, Feroze Khan’s style and Vinod Khanna’s swag. It was nonchalant machismo at its best, supplemented by this assured air of self-confidence. The coolth was extempore. The nerves were real. They were all heroes, in the strictest sense of the word.

And our heroes were out there! On that large rectangular piece of awesomeness that showcased moving images from the worlds we did not belong to, and hypnotized our entire being. We were mortals to them gods. It was a deity-devotee relationship, flourishing in those dark shrines not called multiplexes. The television revolution was yet to happen, VCRs were still glints in their makers’ eyes and nobody knew the spelling of cable TV. Films would actually run for twenty-five and fifty weeks. Going to the cinema halls was picnic without the picnic baskets. The cost of samosas was not equal to the GDP of Ethiopia, and the coffee machines hummed consumable froth in those brawny concoctions. There was romance in the aroma of éclairs, cream rolls and popcorns. Watching a film was living an experience. The theatre walls were grimy, the seats weren’t the most comfortable, the loos were stinky, but none of it mattered. That torch light leading you to your seat, and the anticipation of getting transformed into a whole new world to watch those men and women in action was the only thing that mattered.

Then there was Vinod Khanna. The chiselled looks, the rugged sexuality, the undisguised charm, he was all, and more, that a hero could be. Without trying too hard. It was fascinating to just watch him on screen, and get bewitched. Of course, if you had your carnal glasses on, the fog would tell the complete story.

But nobody wanted to become Vinod Khanna.

Because they knew nobody could ever become Vinod Khanna. He was so unabashedly good looking, and in such an exalted space, that one could not even aspire to be him. Amitabh Bachchan was achievable. The hairstyle and the gait and the walk and the dance moves were replicable. Vinod Khanna was beyond reach. Whatever roles he did, whether it was Shyam singing the melancholic Koi Hota Jissko Apna in Mere Apne or Jabbar Singh mercilessly going on a killing spree in Mera Gaon Mera Desh, the bespectacled Professor Pramod Sharma surrounded by students in Imtihaan or that young scheming sonofabitch Anil conning his mother in Aan Milo Sajna, the oomph always elicited empathy. The cameras and the audiences loved him equally.

Which explains precisely how he could move from playing villains to portraying the hero so effortlessly, and then undertake the journey from being a star to becoming a superstar. Hera Pheri made him a phenomenon. This was followed by a series of blockbusters, including Khoon Pasina, Amar Akbar Anthony, Parvarish, Muqaddar Ka Sikandar and, of course, Qurbani.

Technically, he was not the hero in Qurbani. Hell, he doesn’t even get the girl in the end! But check out the man in the song Hum Tumhen Chaahte Hain Aise. Despite the Feroze Khan aesthetics hovering around a gyrating couple on a fishing boat, Vinod Khanna is all that you would notice. Or want to notice. The casually flowing hair being hit by the sea breeze, the underplayed and non-theatrical expressions, the half-acceptance of the unrequited love, and those lovely longing eyes telling so many tales! You cry for the man despite him not shedding a singular tear. I stand corrected. He was the hero of Qurbani. And perhaps one of the few heroes existing in Hindi Cinema at that time.

And then he left the industry in 1982. Randomly. For the truth. Or whatever.

He came back in 1987 with Satyamev Jayate and Insaaf. A lot had happened in the world in those five years. Vaishali Cinema had shut shop. Jeetendra had given five sleeper hits with the help of his PE teacher. The Bachchan phenomenon was on a decline. The newer generation of actors, including Anil Kapoor, Sunny Deol, Sanjay Dutt and Jackie Shroff, was yet to take off. Mohammed Aziz and Shabbir Kumar were churning out hits. TV antennas were becoming a part of the Indian landscape. Video cassette parlours were mushrooming. The motion pictures industry was going through a major crisis. Filmstars could be hired at a price and consumed in molested VHS tapes grasping for breath in night-long marathon sessions. The heroes were becoming more accessible, everyday commodity.

Not Vinod Khanna, though. He still had the charisma. He still was out there, even in his second coming. While Satymev Jayate did not work, Insaaf was a hit. I still remember how the hall erupted in taalis and seeties when the screen said “RE-INTRODUCING VINOD KHANNA”, celebrating his incredibly potent existence amongst us.

He was back.

But. Something was amiss. His charm seemed laboured, his presence awkward. Not that Hindi cinema or the viewers had evolved in those five years. We were still the same, if not deteriorated by the Jeetendra/ Rajesh Khanna onslaught of the Tohfas and Maqsads of the world. We wanted the Vinod Khanna phenomenon to blast off again for very selfish reasons. We were looking for a hero amongst the crowd of newbies and fallen veterans. In Dayavan, Batwara, Chandni, CID and Jurm, we saw traces of the man we used to worship. The screen presence was still as scorching, the smile could still kill millions. But it was not the same. He was getting old, obviously. It was not about that, though. Or just about that.

I figured what it was in Farishtay, the 1991 film from Anil Sharma of the Tara Singh handpump fame.

Farishtay wasn’t just Dharmendra in a yellow cap and Vinod Khanna in a deep red Stetson hat, dancing on the streets of Mumbai with a bunch of Film City extras half their age in the title song. Farishtay also was the tragic realisation that your gods had feet of clay. Farishtay was a beautiful man desperately clutching on to his stardom, and failing to do so.

Vinod Khanna plays Dheeru to Dharmendra’s Veeru in the film. Beyond the Sholay meta-reference, the film is all kind of odd villains dotting the world, and our saviour-angels taking them head on. Between fighting villains and dancing with heroines, Vinod Khanna’s character has a major fixation for milk. So far so good. Only, milk here refers to things beyond milk. Way beyond milk. “Doodh peene ka mazaa hi kuch aur hai”, declares Dheeru to this buxom bar-girl, “Khaas kar woh doodh kisi tandurust aur doodh-doodh-doodh-doodharu gaai ka ho, aap jaisi” while continuously looking at her breasts, and making a major show of it.

And that’s when my hero became just another guy, just another ageing actor. That crass and vulgar display of his baser emotions wasn’t acting. It was an old man refusing to let go. He may have done forty more films after Farishtay, but Vinod Khanna, my superstar, faded way back in 1991.

Vinod Khanna killed my hero. Vaishali Cinema is becoming a mall. The world, as I knew it, does not exist anymore.

I have made my peace. I hope he does, too.

(first published on Arré)

LOOK, LOOK, this is an article on Ranveer Singh! LOOK NOW. Like, NOW!

Ranveer Singh is everywhere he can be.

So there’s one Ranveer cheekily challenging Baba Ramdev for a dance off, and then being cute about licking his wounds. There’s another mouthing inane godawful rap for one inane godawful brand or the other, taking us back to the Baba-Sehgal-Bali-Brahmbhatt days of the yore, confusing cool with kool. Then there’s one unapologetically Doing The Rex, and making quite a strong statement of it. And there’s one more selling himself out as Ranveer Ching to hawk Chinese products with adrak-ajinomoto gravy. There’s also the guy talking about his araam ka maamla, using his posterior to catch a ball and his anterior to woo them white-skinned extras. All in a day’s work!

If that is not enough Ranveer, he is continuing to sell something or the other every other living moment of his living life, be it Colgate, Jack & Jones, Head & Shoulders, VIVO, Set Wet, Royal Stag, Make My Trip and a few more that I may have missed. Then, of course, there is the man going on all fours at the AIB roast or doing the Hrithik Roshan Bang Bang challenge in the middle of a busy Mumbai intersection or dubsmashing to Taher Khan’s Eye To Eye, complete with the white suit and wig, or dancing on Jabra fan for SRK.

Oh, and he is also doing movies, from Bajirao to Befikre.

He is everywhere. And. He is nowhere.

And THAT is the tragedy of Ranveer Singh. Despite the charm, charisma and the chutzpah, despite the talent and the dushman-ki-dekho-jo-waat-laavli-ness, despite the awards, adulations and ads, and despite the hits and the heroism, he is yet to become a hero. He is NOT a hero. Star, yes. Hero, no. He is still Bittoo from Band Baja Baraat. Chhichhora Yamuna kinaare waala. Bittoo is endearing, totally, but Bittoo gatecrashes even into weddings that he has been invited to for free food, and is an enthu-cutlet for the heck of it. Ranveer does not seem too far from it.

While our man would have us believe there is a method to his madness, the method isn’t really visible. He is loud, he is animated, he is brash, he is charming, he is hahaha funny. And, well, he is enthusiastic to the point of being irritating. The catch is what he thinks is his primary differentiator – his OTT enthusiasm, that is – is actually ending up typecasting him. He is the same guy everywhere, overplaying his overplay. Each of his manifestations across spaces is exactly the same. It is tough to differentiate one rap from another. Or one public antic from another. What damages things further is that he does not know when to stop. Imagine an overtly exuberant energizer bunny which continues to run even when you have taken its batteries off. That’s what Ranveer is. A cheerleader without a cause. Or a pause.

Ranveer Singh wants to be the new age Govinda. Reverse-snobbery can be a sweet thing. In fact, he has been fairly loud about his Govinda affiliations. The entire Rupa Frontline TVC is about him being Raja Baba à la Raja Babu. Tattad Tattad was a fantastic tribute to the G-man. But there is a key difference here. Govinda was Govinda because he was, well, Govinda. The purple suits and the gaudy glasses came naturally to him, and as did those dhinchak moves. Ranveer is too conscious about his play. And that shows. It is as if Ron Weasley has suddenly discovered he is Harry Potter and is trying too hard to be him. When you are cool, you don’t really tell the world about it. Or you do not wear a skirt to a party. He does. Uhm.

So how many Ranveer Singhs do we have in a dozen? Plenty, I would say. All equally delightful. And naturally so. If only he could realise that he is ‘out there’ already, stop doing the oversell and practice some restraint, we would all live happily ever after. Especially Ranveer.

And he should.

Because he is bloody good. He was awesome in Bajirao Mastani, subdued in Lootera, passionate in Ram Leela and fun in Dil Dhadakne Do. The critics have panned Befikre, but loved Ranveer. He has made informed choices and works extremely hard on everything that he picks up. He knows he is an outsider and that, therefore, he has to put in a lot more efforts and be doubly careful that he does not slip up. Precisely why he deserves the accolades more than anybody else. He deserves to be a hero.

AND the day Ranveer Singh stops trying too hard to be a hero, he will become a hero!

(This article was commissioned by ScoopWhoop and was first published on scoopwhoop.com.)

That putridly patriotic token secularism

The furiously fucked mics with the feedbacks, the mandatory Maanyavar kurtas and their grotesque brocade linings highlighting our dashing deshprem, the important people wearing Gujarati-thali sized tricolour badges straight from the 1980s nritya ka akhil bhartiya karyakrams, the five foot nothings with their painted faces and Shiamak swagger, the clueless musicians on the stage silently preaching the tenets of the Rahul Roy duh-ism, the swarms of smartphone equipped parents capturing the glittery profusion of talent that they think their kids are, the random running around of the organisers searching for what must be the codes to the nuclear warheads, the serpentine wires of various diameters miraculously not evolving into another species, the MCs with their Comedy-Nights-with-Kapil sensitivities and Dabbu Shukla Orchestra sensibilities, the abundantly adiposed aunties setting the disco-lit stage on fire, the garlic-impregnated Udupi smell of the Chinese bhel being prepared to be distributed in food packages, the subtle messaging of kids dancing on Main Toh Superman Kar Doon Maa Bhen impressing their Gandhari-Dhritrashtra infused parents, AND the putridly patriotic token secularism everywhere.

Because Republic/ Independence Day.

Ah, the magnificent middleclassness of the Housing Society events, the high point of my life twice every year!